figure 1: the aqueduct.

Caesarea Maritima

Today most people live in cities. Most of these are products of a slow process of growth and development. But there are some rare cases that cities were constructed at once. These planned cities were the vision of great builders. The most famous planned city is probably Washington DC. But history offers more case studies of planned cities. One of them is Caesarea Maritima on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in modern day Israel.[1] When Herod the Great (30-4BC) decided to build Caesarea, he intended to build a perfect city in accordance with his visions. But why did Herod the Great go through all the trouble and expenses of building an entire new city? And what was his perfect city? HISTORY

Before Herod the Great became king of Judea, he supported Mark Antony and the Egyptian queen Cleopatra. But as history tells us, they were defeated by Octavian Caesar, also known as emperor Augustus. Herod the Great shifted alliance and could rule Judea from 30 BC until his death in 4 BC.[2] Herod the Great was not only king of Jewish people, many Greeks, Samaritans and other Hellenised people lived in his land as well. When Herod shifted alliance, his kingdom was enlarged by Augustus. Among these additions were the ruins of Straton Pyros, an old Phoenician town.[3] Here Herod began to build his new capital in 22 BC, and he named it Caesarea in honour of the Roman emperor.[4]

WHY DID HEROD BUILD CAESAREA?

Herod the Great had several political and economical reasons to build this new capital.[5] Each of these reasons had their own effect on the city that Herod built. Herod had two political motives. First, by naming his city after his patron. the emperor Augustus, he dramatically announces his loyalty to the emperor.[6] Herod’s second motive was to prove to his Hellenized subjects that he was not a Jewish king, but a Hellenised king. It was part of being a Hellenised king that one patronized the arts and built cities. He built Caesarea in Greco-Roman style, in contrast to the Jewish city of Jerusalem, so thatr his Hellenized subjects would feel at home in the new city.[7]

The fact that the emperor enlarged Judea was essential to Herod’s economic program.[8] When Herod became king of Judea, Judea had no sea port. The province of Judea was rich in olive oil, wine, dried fruits, balsam oil, salt and bitumen, but non of this could be exported.[9] At Caesarea Herod built a harbour into the open sea. It was a huge building project never done before.[10] But the result was that Judea now had a port that connected the region to the Mediterranean world. Judea grew richer and the income from the port for Herod was enormous. With this income Herod financed the buildings of many other projects like the construction of Temple Mount in Jerusalem. THE RESULTS: HEROD'S PERFECT CITY AT CAESAREA MARITIMA

By building many fortresses, palaces, temples, baths, the city of Caesarea and the harbour of Sebastos (harbour of Caesarea), Herod the Great could show his talent as a royal builder. This was a quality every Hellenised king should have. Herod the Great did see him self more as a Hellenised king, rather then as a Jewish king.[11] So Herod chose to build Caesarea in a Greco-Roman style. Duane W. Roller argues that Herod chose to incorporate Roman elements as a pragmatic move, for the Roman emperor was Herod’s patron [12].

Everything that Herod built, he built big and Caesarea had several very special buildings.[13] The result was a perfect Greco-Roman city placed in a Hippodamian city plan. The most we know about Caesarea is by way of archaeological finds from the past decades but there is one very important literary source. The Jewish historian, Flavius Josephus (37-100AD), wrote one century after Herod the Great about Caesarea. Josephus describes amongst other things how big and special the harbour of Caesarea was. He also is very elaborate on the modern and very effective sewer system that Herod built at Caesarea.[14]

|

|

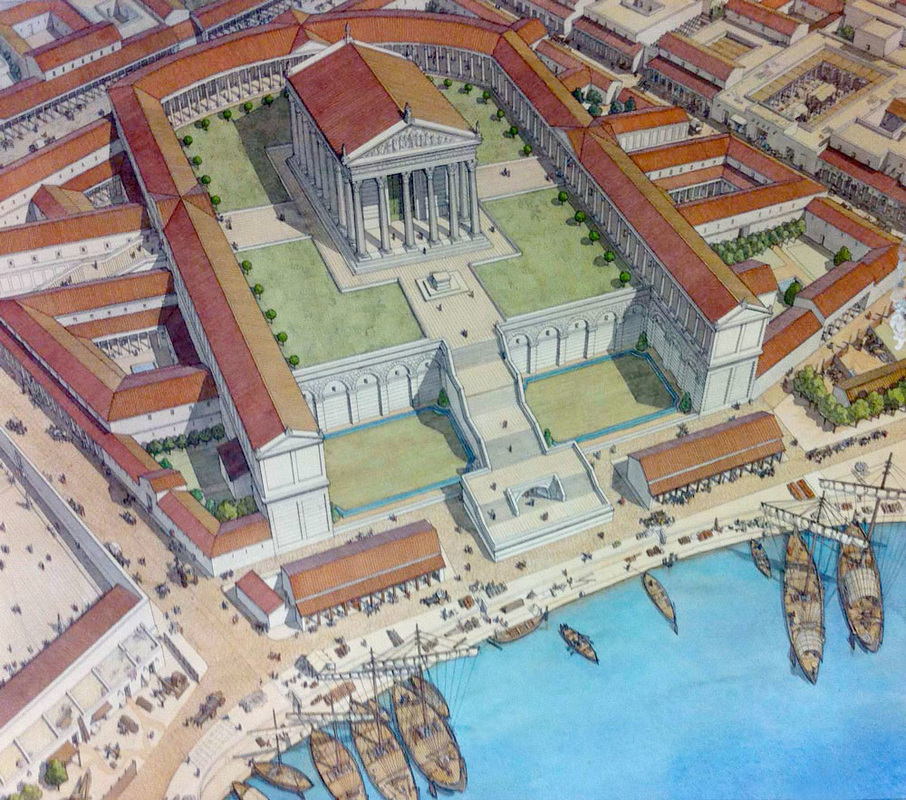

Figure 2: areal view of the harbour. Figure 3: the south side of the hippodrome.

PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND DE DECORATION OF THE CITY

Beside these special buildings mentioned above, the city had of course an agora, which is still unfound today. Mentioned and praised by Josephus, Herod built an elaborate sewer system under the entire city which was cleansed by the sea.[25] To supply the city, the fountains and the gardens with water Herod had a 10 miles long aqueduct constructed. The main street and side streets, the cardo maximus and the decumanus maximus was decorated with colonnades. Typical is that Herod built mostly with the local kurkar stone. When the Romans came, they transformed the city in to a marble city.

As perfect city, Herod built a Greco-Roman city. By building a Greco-Roman city Herod hoped to appeal to his Hellenised subjects. By naming the city after the emperor Herod dramatically showed his loyalty. With Caesarea, Herod gave Judea the port it needed and Herod proved to be a master builder.

None of the traditional elements of a Greek poleis or Roman city were absent in Caesarea. The harbour was a masterpiece and no effort was spared for the temple and palace either. |

figure 4: A RECONSTRUCTION OF CAESAREA

figure 5: the aqueduct figure 6: the crusaders walls figure 7: the theatre

|

REFERENCES

Figure sources:

figure 1: https://www.flickr.com/photos/bigluzer/2290456524 figure 2:http://web.uvic.ca/~jpoleson/ROMACONS/Caesarea2005.htm Figure 3: http://www.urantiabook.org/photo-galleries/life-of-jesus/caesarea-maritima/content/_4148873_HDR_web_large.html Figure 4: https://www.pinterest.com/alkkndr/ancient-world-map-caesarea-maritima-israel/ figure 5: http://www.nationalgeographic.com/explorers/lost-places-gallery/#/cesarea-maritima-lost-worlds_45947_600x450.jpg figure 6:https://www.tripadvisor.com/LocationPhotoDirectLink-g297742-d379315-i65149681-Theatre_at_Caesarea_National_Park-Caesarea_Haifa_District.html figure 7:http://www.arqueologiabiblica.tv/ |