Persepolis and zoroastrianism

abstract

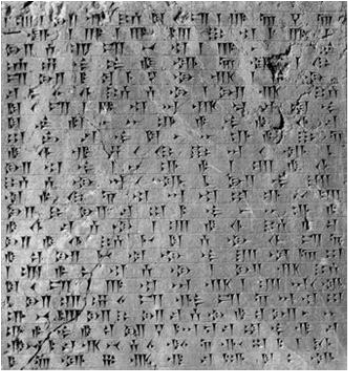

The palace city of Persepolis, built during the reign of Darius I, was one of the main capitals of the Achaemenid Empire. [1] On the southern wall, an Elamite inscription is written that explains how Darius viewed his city: “And I built the city safe, beautiful and adequate. Just as I intended to.” [2] Also, in that same inscription, Ahura Mazda – supreme godly being of Zoroastrianism – was said to have been the one who commissioned the building. This implies that the city of Persepolis and Zoroastrianism were linked. Other examples – like Darius’ tomb at Naqsh-I Rustam and the lion and bull relief – confirm this thesis . Nowadays, though fatally burnt by Alexander the Great in 330 BCE [3], the complex still stands as one of the highlights of Achaemenid royal architecture.

|

Introduction |

This weebly focuses on Persepolis in the time of the Achaemenids – more specifically: Darius and Xerxes, i.e. 522 until 465 BCE – and how they used Zoroastrian elements in erecting their palace city. Firstly, emphasis will be put on how the city itself came to be: we go from Cyrus the Great to how Darius and Xerxes respectively built and expanded the city. Secondly, Zoroastrianism will be introduced: who were its “key players” and what was this religion all about? Thirdly, one microstudy will be analyzed in which Zoroastrianistic elements are incorporated - what could the usage of those elements mean? This weebly will outline some of the reasons which could be behind this given link. True, we may never fully discover the true story of why the city and its architecture were built in the first place, but that should not keep us from wondering.

|

BUILDING PERSEPOLIS

[Fig. 2] Depicture of Darius I the Great

[Fig. 2] Depicture of Darius I the Great

The Achaemenids started their dynasty with Cyrus the Great; he united different Persian tribes and successfully set aside the Medes. His son and successor Cambyses tried to expand the empire. While fighting in Egypt, Cambyses tragically died when he tried to return to deal with a revolt at home. It was his son Darius who stood as victor in the mayhem, for he defeated his rival Bardiy – designating him as “the Lie”, which was a Zoroastrian connotation – and for some reason chose to start building Persepolis in 518 BCE. [4]

Persepolis was built on rocky grounds. Therefore its builders had to work with different levels, which are still traceable in the palace complex. Among Persepolis’ most intriguing architecture is the broad dual stairway that gave entrance to the terrain. Standing on top of it one could see the Gate of All Nations with Xerxes’ building inscription on it. After crossing the gate on the left, visitors could be heading for the Apadana – literally the most elevated place of the city – where the king most likely received his important guests. In close distance of the Apadana was the Hall of a Hundred Columns of which scholars differ on what its function exactly was. [5]

Persepolis was built on rocky grounds. Therefore its builders had to work with different levels, which are still traceable in the palace complex. Among Persepolis’ most intriguing architecture is the broad dual stairway that gave entrance to the terrain. Standing on top of it one could see the Gate of All Nations with Xerxes’ building inscription on it. After crossing the gate on the left, visitors could be heading for the Apadana – literally the most elevated place of the city – where the king most likely received his important guests. In close distance of the Apadana was the Hall of a Hundred Columns of which scholars differ on what its function exactly was. [5]

Zoroastrianism

[Fig. 3] Ahura Mazda's image shows itself frequently

[Fig. 3] Ahura Mazda's image shows itself frequently

Somewhere between 1500 en 1000 BCE Zarathustra is thought to have come up with a new religion called Zoroastrianism. Dwelling to a great extent on religious habits of Indo-European peoples, its most rigorously element was that – instead of emphasizing all different sorts of cult and nature gods – there was one supreme godly being: Ahura Mazda. Zoroastrianism, though in essence monotheistic, also presented a dualistic worldview: Ahura Mazda was in a constant fight with the evil Angra Mainyu. Yes, there were other godly figures, but they all were said to derive directly from Ahura Mazda.[6]

Persepolis is filled with inscriptions and reliefs with Ahura Mazda. For that reason mainly, scholars presume that Darius was an adherent of Zoroastrianism. However, some scholars cannot help raising their eyebrows when reading "Ahura Mazda, together with all the gods” on several inscriptions, though most of these scholars tend to incline that this must have been out of sole respect for local gods. After all, the Achaemenids did not try to impose Zoroastrianism on the inhabitants of their empire. Considering Xerxes, there is more reason to have second thoughts about his monotheistic status, since he often misused Zoroastrian concepts in inscriptions. [7]

Persepolis is filled with inscriptions and reliefs with Ahura Mazda. For that reason mainly, scholars presume that Darius was an adherent of Zoroastrianism. However, some scholars cannot help raising their eyebrows when reading "Ahura Mazda, together with all the gods” on several inscriptions, though most of these scholars tend to incline that this must have been out of sole respect for local gods. After all, the Achaemenids did not try to impose Zoroastrianism on the inhabitants of their empire. Considering Xerxes, there is more reason to have second thoughts about his monotheistic status, since he often misused Zoroastrian concepts in inscriptions. [7]

Lion versus bull relief

[Fig. 4] How to interpret the lion attacking a bull relief

[Fig. 4] How to interpret the lion attacking a bull relief

One of the most interesting reliefs in Persepolos is undoubtedly the lion versus bull relief. This depiction can be found no less than twenty-six times in Persepolis. Obviously, a bull is attacked by a lion. The lion tries to tear the bull’s loins by grabbing into the bull by its claws. What can this image mean? There are multiple explanations possible. It could be that the image directly refers to Zoroastrianism, for the bull is not only an important creature within Zoroastrian religion, but also in earlier Indo-European times.[8] On the other hand, the bull and lion could also respectively represent the moon and sun, thereby reflecting a battle between darkness and light. Another interesting thought was presented by Ilya Gershevitch, who interpreted the picture in an astronomical way: the lion star sign is entering the bull star sign and therefore the image represents the arrival of Nowruz – the festival of New Year that happened to be the most sacred festival for Zoroastrians. Or was this image merely to demonstrate the power of the king over his people? [9]

Conclusion

For sure, Persepolis and Zoroastrianism are linked to one another. Besides the lion bull relief, there are more examples to be found in the city: Darius' tomb at Naqsh-i Rustam a few miles outside Persepolis, the procession relief, several inscriptions to be found everywhere, the Gate of All Nations et cetera. Why Darius and Xerxes used Zoroastrian elements is not sure; there is no scholarly consensus in this debate. What did Darius mean when he referred to "all the gods"? Was Xerxes just as much a Zoroastrianist as his father? The link between Persepolis and Zoroastrianism is hereby secured; may others dwell on different challenging themes.

|

|

|

sources references

[1] Matt Waters, Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire, 550-330 BCE (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 110.

[2] Ali Mousavi, Persepolis: Discovery and Afterlife (Boston en Berlijn: Walter de Gruyter, Inc., 2012).

[3] Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg, “Den wereltvorst een vuyle streek aan sijn eercleet” Oratie (Utrecht: Onderwijs Media Instituut, 1991) 7.

[4] Ilya Gershevitch ed., The Cambridge History of Iran; Volume 2: The Median and Achaemenian Periods (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985).

[5] Ali Mousavi, “Why Darius built Persepolis?”, Achaeology Odyssey 8, no. 6 (2005), 24-25.

[6] Mary Boyce, Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices (Londen, Boston en Henley: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979).

[7] Stephen Bertman, Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia (New York: Facts on File, Inc., 2003).

[8] Mary Boyce, A History of Zoroastrianism. Volume Two: Under The Achaemenians (Leiden en Keulen: E.J. Brill, 1982), 106.

[9] Geschevitch, ed., 738.

[2] Ali Mousavi, Persepolis: Discovery and Afterlife (Boston en Berlijn: Walter de Gruyter, Inc., 2012).

[3] Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg, “Den wereltvorst een vuyle streek aan sijn eercleet” Oratie (Utrecht: Onderwijs Media Instituut, 1991) 7.

[4] Ilya Gershevitch ed., The Cambridge History of Iran; Volume 2: The Median and Achaemenian Periods (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985).

[5] Ali Mousavi, “Why Darius built Persepolis?”, Achaeology Odyssey 8, no. 6 (2005), 24-25.

[6] Mary Boyce, Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices (Londen, Boston en Henley: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979).

[7] Stephen Bertman, Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia (New York: Facts on File, Inc., 2003).

[8] Mary Boyce, A History of Zoroastrianism. Volume Two: Under The Achaemenians (Leiden en Keulen: E.J. Brill, 1982), 106.

[9] Geschevitch, ed., 738.

media references

- Header: http://www.nationalgeographic.com.es/medio/2014/11/14/persepolis1_2000x1603.jpg

- [Fig. 1]: http://www.livius.org/a/1/inscriptions/DPf.jpg

- [Fig. 2]: http://www.ancient.eu/uploads/images/899.jpg?v=1431036032

- [Fig. 3]: http://www.livius.org/a/1/iran/faravahar.jpg

- [Fig. 4]:http://www.livius.org/a/iran/persepolis/apadana-northstairs/apadana_n_stairs_lion-bull.JPG

- [Fig. 1]: http://www.livius.org/a/1/inscriptions/DPf.jpg

- [Fig. 2]: http://www.ancient.eu/uploads/images/899.jpg?v=1431036032

- [Fig. 3]: http://www.livius.org/a/1/iran/faravahar.jpg

- [Fig. 4]:http://www.livius.org/a/iran/persepolis/apadana-northstairs/apadana_n_stairs_lion-bull.JPG

Further reading?

- Babaie, Sussan en Grigor, Talinn ed. Persian Kingship and Architecture. Londen: I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd., 2015.

- Curtis, John en Simson, St John ed. The World of Achaemenid Persia: History, Art and Society in Iran and the Ancient Near East. Londen: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd., 2010.

- Gershevitch, Ilya. “Zoroaster’s Own Contribution”. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 23, no. 1 (1964).

- Trümpelmann, Leo. Ein Weltwunder der Antike: Persepolis. Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 1988.

- Vuurman, Corien J.M. Fascinatie voor Persepolis: Europese perceptive van Achaemenidische monumenten in schrift en beeld, van de veertiende eeuw tot het begin van de twintigste eeuw. Proefschrift. Gronsveld: Barjesteh van Waalwijk van Doorn & Co’s Uitgeversmaatschappij, 2014.

- Curtis, John en Simson, St John ed. The World of Achaemenid Persia: History, Art and Society in Iran and the Ancient Near East. Londen: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd., 2010.

- Gershevitch, Ilya. “Zoroaster’s Own Contribution”. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 23, no. 1 (1964).

- Trümpelmann, Leo. Ein Weltwunder der Antike: Persepolis. Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 1988.

- Vuurman, Corien J.M. Fascinatie voor Persepolis: Europese perceptive van Achaemenidische monumenten in schrift en beeld, van de veertiende eeuw tot het begin van de twintigste eeuw. Proefschrift. Gronsveld: Barjesteh van Waalwijk van Doorn & Co’s Uitgeversmaatschappij, 2014.