Corinth

Introduction

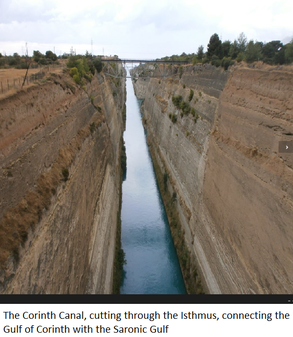

The Greek city of Corinth was one of the wealthiest cities of ancient times. It held the reputation of being an extremely prosperous city from at least 700 BC. Despite its ups and downs, it still maintained a leading position in the Greek world by 146 BC. At this time the Roman consul Lucius Mummius let his army sack Corinth in order to quell a desperate Greek revolt, razing the buildings, killing or selling into slavery its inhabitants. Mummius plundered the city and took with him the greatest symbols of Corinthian wealth. The most notable part of the booty were the numerous statues, paintings and other works of art. Mummius had those shipped back in large quantities to Rome and subsequently displayed them during his triumph. This was unusual, since most commanders to whom was awarded a triumph displayed defeated and humiliated enemies. Afterwards, he distributed those artworks among cities in the various parts of the Mediterranean under Roman hegemony. In 44 BC, Corinth was refounded by Julius Caesar and rose to prominence once again. The Romans would later make it the capital of their Greek province. Roman Corinth is well-known from archaeological remains (nearly all of the remains that can be seen at the archaeological site date from the Roman period) and from the Pauline Epistles to the Corinthians. Likewise, most reconstructions made today of what Corinth might have looked like show Roman Corinth. This webpage, however, will focus on Greek Corinth and its destruction by the Romans. The question it will try to answer is: why did Lucius Mummius decide to destroy Corinth? This destruction marked a significant departure from the way the Romans had dealt with rebellious cities in Greece before. The second part of my research is: in what ways did Mummius benefit from the stolen Corinthian art, since the way he displayed it during his triumph was, apparently, a novelty?

The wealth of Greek Corinth

Destruction of Corinth

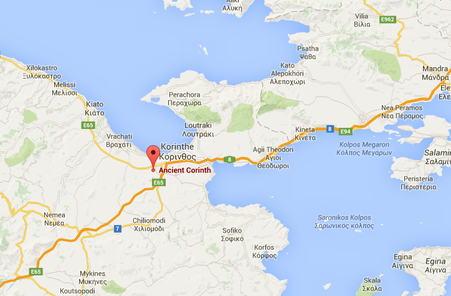

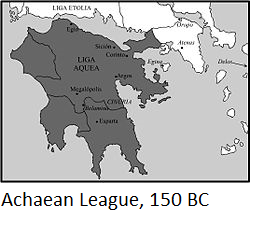

In 146 BC, after a short uprising by the Achaean League against the Roman dominance in the region, the Roman consul Lucius Mummius defeated the League's army at the Battle of Corinth and destroyed the city, killing or selling into slavery the inhabitants and taking large amounts of booty. During the time of the Achaean war, Corinth was the Achaean League's chief city[4]. It was also the first city of the league an army marching from Macedon in the north would encounter (see picture). This seems to be the main reason why the Greeks chose to make their stand at Corinth and also the most logical explanation to Mummius' act of destroying the city to make an example. It does, however, not explain why an example had to be made at all, as this was quite contrary to previous Roman practice (although Carthage had undergone a similar fate earlier in the same year, when it was taken and destroyed by Scipio Aemilianus, Mummius' political rival)[5]. Not only Corinth, but other cities were punished as well. According to Pausanias, Mummius tore down the walls of all cities that had fought against Rome, and seized their arms[6]. Besides, he also plundered other cities as far away as Boeotia[7]. Still, Corinth was the only rebellious city that was met with such a harsh treatment. Actually, Mummius may have intended to destroy Corinth from early on. The rebellion of the Achean League was more or less provoked by Roman demands; the senate decreed that neither Sparta (which was in fact not part of the league) nor Corinth itself should belong to the Achaean League [8]. This was unacceptable. Earlier that year, Mummius's fellow consul and rival Scipio Aemilianus had conquered and destroyed Carthage. Mummius seems to have been in a hurry to get to Greece in time before the general who had defeated the Macedonians, Quintus Caecilius Metellus, would have had a chance to end the rebellion by use of force or negotiation. The historiographical tradition emphasizes that Mummius stole Metellus' gloria, after Metellus had performed the decisive military actions[9].

The spoils of Corinth

But why plunder Corinth? Mummius would have been hailed a conqueror just as much if he had just defeated the Greeks on the battlefield and left their cities intact. It is here that Corinthian art comes into play. As noted by Eutropius, Mummius displayed the artworks during his triumph, while his rivals Scipio and Metellus showed their defeated and humiliated opponents [10]. This last practice was customary [11]. After his triumph, Mummius distributed the booty among several different communties and cities in Italy, Greece, and even further away, from Italica in Spain to Pergamum in the east [12]. In the literary sources, Mummius is mostly portrayed as someone lacking an appreciation of the Greek culture, unable to understand the value of the artworks of Corinth. These ancient sources attribute his generosity in distributing booty to this lack of understanding of the art [13]. A well-known example is the story told by Velleius Paterculus that Mummius warned the contractors who were to ship the art back to Rome that if they lost the artworks, they would have to replace them with new ones themselves [14]. His generosity is often contrasted with his personal abstinence [15]. Back in Rome, Mummius built a temple (which was customary) for Hercules Victor and had numerous works of art displayed throughout the city [16]. Any class of viewers of Mummius' munificence, from senators to plebeians, could be a political force [17]. In 142 BC, he held the censorship (together with his rival Scipio Aemilianus) [18]. It is suggested that Mummius' munificence was part of his electoral campaign. However, from the communities outside of Rome that received his gifts, very few possessed the franchise [19]. In contrast to previous Roman conquerors in the Greek east, who just reaped the honors and reinforced the Roman hegemony, Mummius used Greek art and inscriptions to make a positive statement towards the conquered Greeks [20]. This corresponds to the common Roman rhetoric of friendship and alliances with conquered peoples that the Romans had used to build their dominion for a long time. Mummius thus more or less shared his victory over the Greeks with Rome's new allies, the Greeks. Indeed, some of Corinth’s art probably ended up in Isthmia, just a few miles away from Corinth, and other cities which Mummius had plundered, like Thespiae, received gifts too [21]. Finally, to explain Mummius' generosity to Rome's Italian allies, we take a look at the cause of the Social War, about fifty years later. This war may have started because the Italian cities felt excluded from the empire [22]. Mummius' extensive placement of Corinthian plunder achieved three things: it promoted him as a philhellene, a friend of the Greeks; he asserted his power; and he was able to effectively respond to the popularity of his rival, Scipio Aemilianus [23].

Notes

[1] Homer, Iliad 2.570

[2] Thucydides, Histories 1.13.5

[3] Thucydides 1.13.2

[4] Dunstan(2011) 87

[5] Kendall (2009) 169

[6] Pausanias, Description of Greece 7.16.9

[7] Yarrow (2006) 66

[8] Pausanias 7.14.1

[9] Yarrow (2006) 59, n. 7

[10] Eutropius, Breviarium Historiae Romanae 4.14

[11] Kendall (2009) 169-170

[12] Yarrow (2006) 57

[13] Yarrow 58

[14] Velleius Paterculus, Historiae 1.13.3-5

[15] Yarrow (2006) 61

[16] Yarrow (2006) 60

[17] Yarrow (2006) 61

[18] Kendall (2009) 169

[19] Yarrow (2006) 61

[20] Yarrow (2006) 67

[21] Yarrow (2006) 66

[22] Yarrow (2006) 68

[23] Kendall (2009) 174

[2] Thucydides, Histories 1.13.5

[3] Thucydides 1.13.2

[4] Dunstan(2011) 87

[5] Kendall (2009) 169

[6] Pausanias, Description of Greece 7.16.9

[7] Yarrow (2006) 66

[8] Pausanias 7.14.1

[9] Yarrow (2006) 59, n. 7

[10] Eutropius, Breviarium Historiae Romanae 4.14

[11] Kendall (2009) 169-170

[12] Yarrow (2006) 57

[13] Yarrow 58

[14] Velleius Paterculus, Historiae 1.13.3-5

[15] Yarrow (2006) 61

[16] Yarrow (2006) 60

[17] Yarrow (2006) 61

[18] Kendall (2009) 169

[19] Yarrow (2006) 61

[20] Yarrow (2006) 67

[21] Yarrow (2006) 66

[22] Yarrow (2006) 68

[23] Kendall (2009) 174

References

Dunstan, William E. (2011). Ancient Rome. Rowman & Littlefield publishers, inc.

Kendall, Jennifer. 2009. "Scipio Aemilianus, Lucius Mummius, and the politics of plundered art in Italy and beyond in the 2nd century B.C.E." Etruscan Studies : Journal Of The Etruscan Foundation 12, 169-181.

Yarrow, Liv Mariah. 2006. "Lucius Mummius and the spoils of war." Scripta Classica Israelica : Yearbook Of The Israel Society For The Promotion Of Classical Studies 25, 57-70.

Kendall, Jennifer. 2009. "Scipio Aemilianus, Lucius Mummius, and the politics of plundered art in Italy and beyond in the 2nd century B.C.E." Etruscan Studies : Journal Of The Etruscan Foundation 12, 169-181.

Yarrow, Liv Mariah. 2006. "Lucius Mummius and the spoils of war." Scripta Classica Israelica : Yearbook Of The Israel Society For The Promotion Of Classical Studies 25, 57-70.

Images

Image 1 (header): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Corinth#/media/File:CorintoScaviTempioApollo.jpg

Image 2 (Corinth Canal): own picture

Image 3 (Corinthian order): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corinthian_order#/media/File:CorinthianOrderPantheon.jpg

Image 4 (Achaean League): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Achaean_League#/media/File:La_Liga_aquea_en_150_aC.jpg

Image 2 (Corinth Canal): own picture

Image 3 (Corinthian order): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corinthian_order#/media/File:CorinthianOrderPantheon.jpg

Image 4 (Achaean League): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Achaean_League#/media/File:La_Liga_aquea_en_150_aC.jpg