Phaistos

Strong but refined

Introduction

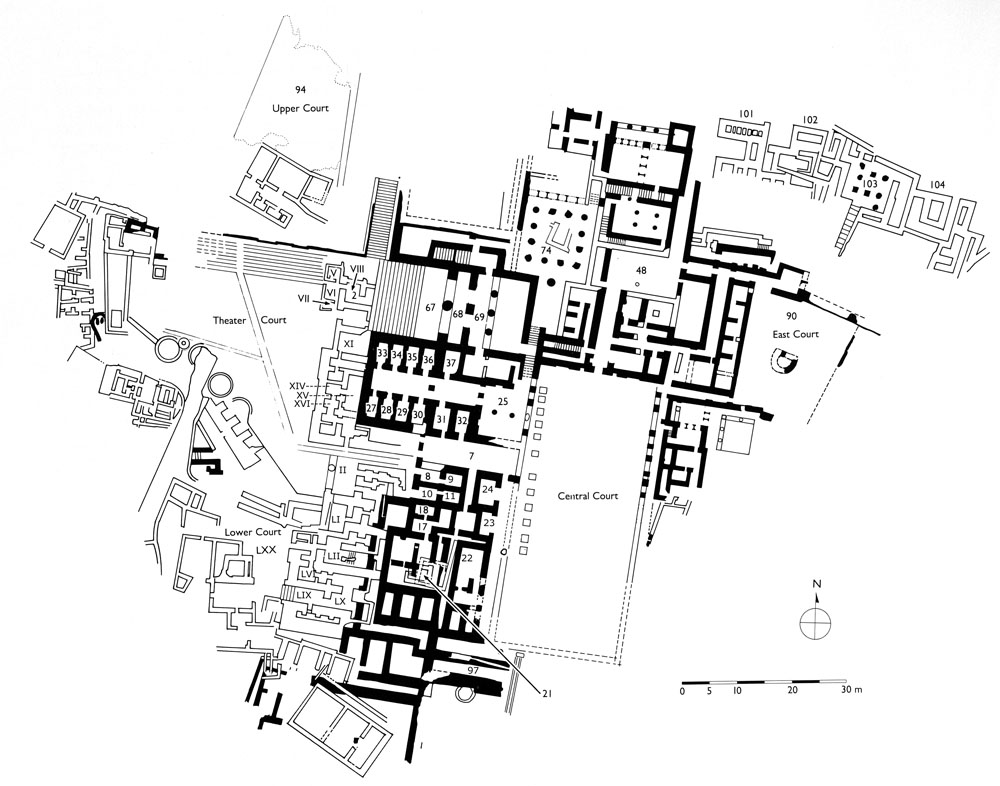

When we think of Minoan Crete, the first city that comes to mind is Knossos, in the north of the island. But within roughly the same period of time, there was also an important city in the south: Phaistos. From about 4000 BC (the Late Stone Age), Neolithic villages were scattered on top of and around Kastri Hill on the fertile Messara plains. Later, around 2000 BC, Phaistos was founded on top of the Kastri Hill in the fertile Messara plains, consisting of one big 'palace complex', resembling a labyrinth [Castleden, 1990]. The largest and most important Minoan center in the second millennium BC, save for Knossos, Phaistos has not been subject to extensive restorations, hence its title of being the most authentic (ruins of a) Minoan city we can marvel at nowadays.

An interesting but elusive question is how this fascinating city tried to maintain its own identity, especially in the polis period, when other cities like Gortyn and Haghia Triada overshadowed Phaistos. To research this, we should first examine the elements that are important in shaping a city's common identity, then we will look at which of these things we can find, and what these things say about the identity of Phaistos. Since several areas have yet to be excavated, some of our answers must remain hypothetical. But much is known about the palatial complex, in its different phases, so I'd like to take that as our most important source. [1]

An interesting but elusive question is how this fascinating city tried to maintain its own identity, especially in the polis period, when other cities like Gortyn and Haghia Triada overshadowed Phaistos. To research this, we should first examine the elements that are important in shaping a city's common identity, then we will look at which of these things we can find, and what these things say about the identity of Phaistos. Since several areas have yet to be excavated, some of our answers must remain hypothetical. But much is known about the palatial complex, in its different phases, so I'd like to take that as our most important source. [1]

Founding stories |

For our fist step, I'd like to follow John Ma's theorem [2] that a group of people can build a collective memory (and thus their own identity) in three different ways: through foundation stories, through place (monumentalizing), and through place in a more diffuse sense (like gestures, rituals, stories, and spaces).

Let us start with the foundation stories, do we have any left? Yes, we do, even more than just one, but all of them were written down in a much later period, so we can't be sure that these stories were the same ones the inhabitants of Phaistos had. According to the historian Diodorus Siculus, Phaistos was founded by the mythical king Minos, who also founded Knossos and Kydonia. It was told that his brother Rhadamanthys was the first king of Phaistos. [3] Other stories tell that not Minos has founded the city, but Phaistos, son of Hercules (or of Ropalus, the text isn't totally clear about this) [4] founded the city. |

|

What about the physical evidence we have left, or indications of objects that maybe once existed? Nowadays we can still see the ruins of the palace complex of Phaistos, even different building phases of it, which let us know that the palace was in use over a long period of time. More downhill there have been found remnants of houses, but the relation between these houses and the palatial complex is still uncertain. The fact that a lot of these houses were destroyed, while trying to bring the structure of the palace complex to light, is the main reason for this uncertainty. [5] Besides the palace complex we also have some (tholoi) graves left, but almost all of them are from the early times of the Minoan period, so they don't have a lot to add to our research, since we are looking at the late Minoan period until the polis period. One tomb that can add something, would be the Kamilari Tomb (it actually consisted of three tholoi located very near Phaistos and Haghia Triada), that even though it was build in the Middle Minoan period, which is considerably later than all other tholoi, and was still used during Mycenaean times. [6] According to Andrea Vianello (2000) the fact that they were still using the tomb may indicate that at the time of the Mycenaean invasion they wanted to recall their old manner of burying their dead, and we can say they did this to preserve their own identity.

|

Monuments and other buildings

|

zoom in on the Palace

|

The building of the first palace has been estimated around 2000 BC. Probably due to an earthquake (and a following fire) the palace was, along with other Minoan palaces, destroyed around 1700 BC. They tried to rebuild the old palace, but it failed, probably due to more earthquakes, but the city continued to flourish. A new bigger palace began to be built—and rebuilt, because there were still earthquakes—in the following 200 to 300 years, but this costly palace partly made of marble was never finished. In the period of 1450-1350 BC this palace was also destroyed, probably by an earthquake, as with all the other palaces on Crete. [7] Another option for this destruction could have been the Mycenaeans who invaded Crete around the same time, or it could have been a combination of both factors.

Some interesting parts of the palace are the storage rooms, and the processional way that goes through the theater area towards the upper court which looks out over Mount Ida. The storage rooms contained a lot of big storage jars, pithoi, holding things like olive oil and other agricultural products. A lot of these pithoi were standing in sight, so it seems as if they wanted to display their wealth. Besides these storage pots, there were also a few storage silos for grain, located at the south border of the theater area. |

|

In the Minoan culture no temples have been found, but they did have peak sanctuaries and cave sanctuaries, like at Mount Ida, where a lot of votive cult offerings have been found and where Zeus was hid by his mother Rhea according to some versions of the myth. [8] Taking this in account when we look at the processional way, that leads towards the upper court which looks out on Mount Ida, we can conclude that the way was used for religious processions. By structuring the palace like this, they made Phaistos a place that was an important religious centre. Around the 7th century not only renovated streets were made, but also a temple for Rhea/Leto/the Great Mother was built, so there is probably (an attempt to) a continuity of role as a religious centre. [9]

On the other hand, Phaistos was made a very strategic place, because of its positioning on top of the Kastri hill, and with this their ability to see as far north as the Psiloritis mountains, over the extensive Messara Plains, and as far south as the Asterousi mountains, apparently designed to be able to do that. [10] Stories about a city are very important as well to make a common identity. The stories we have about Phaistos are from Homer. In the period between the destruction of the second palace and the age of the Greek polis, the city was well populated, and participated in the Trojan War according to him, and after these stories the Dark Ages start. [11] [12] He also talks about battlements, which gives us the image of a large polis-like fortified settlement, but this doesn't necessarily mean that Phaistos at the time actually had a wall, because also of Gortyn Homer says that it has a wall, but that wall wasn't built in reality until the Hellenistic period. [13] Nonetheless the picture stands. Haghia Triada, whose royal villa was built in the 16th century, could have competed with the role of religious centre, as the site also had a religious function in the Geometric period. [14] The also nearby Gortyn flourished in the 1st millennium, but existed already in the Minoan period, as it appears too in Homer (he calls it strong-walled) [15] and it surpasses Phaistos in the 1st millennium as the chief power in the Messara, and even annihilates Phaistos around 150 BC. [16] Even though Phaistos was suppressed by these two cities, they still got their own coins in the 4th century and expanded in the 11th to the 7th century. [17] Often used motives on the currency are i.a.: a bull, Herakles (hero of Phaistos), Europa, and the (winged) bronze giant Talon. [18] With these motives they don't only conform to the general Cretensian motives, but at the same time they also show the importance of these myths for themselves. |

Diffuse places: ritual, placement, stories

Problems? |

Conclusion

|

Its advantageous position on top of the Kastri Hill made Phaistos able to stand tall, in later periods it gained also a defensive wall. This made Phaistos well prepared for attacks. In the age of the polis, Phaistos was largely overshadowed by its neighbouring city Hagia Triadha, but continued to exist. It has even been renovated in the 8th century, looking at the paved streets and a new built temple for Rheia. This indicates that the palace still was an important (religious) centre and that it was frequented regularly, and also taking the expansion in the Geometric period of the village around the palace in account, it probably still was an important centre overall. Haghia Triada may have been a more important religious centre, Phaistos still was a good alternative. In the late Classical age they got their own currency, with motives that point at their rich mythical history.

For now we can say that Phaistos kept trying to hold on to their image as a strong and religious centre city with making new buildings like the temple of Rhea and remembering motives of long ago (but still present) on their coins, but in the end struggled to keep up with other places like Haghia Triada and Gortyn and eventually fell for good. |

Media:

Picture 1: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/2f/Phaistos_01.jpg

Picture 2: http://www.ancient.eu/uploads/images/348.png?v=1431033913

Picture 3: https://classconnection.s3.amazonaws.com/973/flashcards/819973/png/phaistos_%28lm%291332208121825.png

Picture 4: http://www.odysseyadventures.ca/articles/knossos/006.magazines02.jpg

Picture 5: http://ancient-greece.org/images/ancient-sites/phaistos/images/152_5265_jpg.jpg

Picture 6: http://www.grisel.net/images/greece/Phaestos30_17.JPG

Youtube movie: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FS2x8Y5uPu4

Picture 1: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/2f/Phaistos_01.jpg

Picture 2: http://www.ancient.eu/uploads/images/348.png?v=1431033913

Picture 3: https://classconnection.s3.amazonaws.com/973/flashcards/819973/png/phaistos_%28lm%291332208121825.png

Picture 4: http://www.odysseyadventures.ca/articles/knossos/006.magazines02.jpg

Picture 5: http://ancient-greece.org/images/ancient-sites/phaistos/images/152_5265_jpg.jpg

Picture 6: http://www.grisel.net/images/greece/Phaestos30_17.JPG

Youtube movie: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FS2x8Y5uPu4

References:

1: Watrous, Hadzi-Vallianou, Blitzer (2004) 525-526

2: J. Ma (2009) ‘City as Memory’, in G. Boys-Stones et al., The Oxford Handbook of Hellenic Culture, Oxford 249-259.

3: Diodorus Siculus, Biblioteca Historica, book V.

4: Pausanias, Book of Greece, book II; Stephanus of Byzantium

5: F. Longo e.a. (2011) Progetto Festòs. Ricognizioni archeologiche di superficie: le campagne 2007-2009.

6: Andrea Vianello (2000) Some notes about Kamilari Tholos.

7: Website of the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports, Palace of Phaistos (read on 31-03-2016)

8: William Smith, ed. (c. 1873). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology. John Murray.

9: La Rosa (1996) Per la Festòs di età arcaica. Studi Miscellanei. Studi in memoria di Lucia Guerrini 68-82; CUCUZZA 2005, 300

10: C.M. Hogan (2007) Phaistos Fieldnotes. The Modern Antiquarian.

11: Homer, Iliad, B 648

12: Homer, Odyssey, C 269

13: Daniela Lafevre (2007) Les débuts de la polis: l'exemple de Phaistos (Crète). KTÈMA Civilisations de l'Orient, de la Grèce et de Rome antiques, Université de Strasbourg, pp.467-495.

14: Website of the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports, Royal Villa at Agia Triada (read on 01-04-2016)

15: Homer, Iliad, B 646

16: Strabo, Geografica X, 4.14

17: N. Cucuzza (1998) Geometric Phaistos: A Survey. In post-Minoan Crete. Proceedings of the first colloquium on post-Minoan Crete. Held by the British School at Athens and the Institute of Archaeology. University College London, ed. W.G. Canavagh and M. Curtis, London, pp. 62-68.

18: http://www.wildwinds.com/coins/greece/crete/phaistos/i.html (read on 01-04-2016)

1: Watrous, Hadzi-Vallianou, Blitzer (2004) 525-526

2: J. Ma (2009) ‘City as Memory’, in G. Boys-Stones et al., The Oxford Handbook of Hellenic Culture, Oxford 249-259.

3: Diodorus Siculus, Biblioteca Historica, book V.

4: Pausanias, Book of Greece, book II; Stephanus of Byzantium

5: F. Longo e.a. (2011) Progetto Festòs. Ricognizioni archeologiche di superficie: le campagne 2007-2009.

6: Andrea Vianello (2000) Some notes about Kamilari Tholos.

7: Website of the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports, Palace of Phaistos (read on 31-03-2016)

8: William Smith, ed. (c. 1873). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology. John Murray.

9: La Rosa (1996) Per la Festòs di età arcaica. Studi Miscellanei. Studi in memoria di Lucia Guerrini 68-82; CUCUZZA 2005, 300

10: C.M. Hogan (2007) Phaistos Fieldnotes. The Modern Antiquarian.

11: Homer, Iliad, B 648

12: Homer, Odyssey, C 269

13: Daniela Lafevre (2007) Les débuts de la polis: l'exemple de Phaistos (Crète). KTÈMA Civilisations de l'Orient, de la Grèce et de Rome antiques, Université de Strasbourg, pp.467-495.

14: Website of the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports, Royal Villa at Agia Triada (read on 01-04-2016)

15: Homer, Iliad, B 646

16: Strabo, Geografica X, 4.14

17: N. Cucuzza (1998) Geometric Phaistos: A Survey. In post-Minoan Crete. Proceedings of the first colloquium on post-Minoan Crete. Held by the British School at Athens and the Institute of Archaeology. University College London, ed. W.G. Canavagh and M. Curtis, London, pp. 62-68.

18: http://www.wildwinds.com/coins/greece/crete/phaistos/i.html (read on 01-04-2016)

|

R.C.F.

|