Augusta Treverorum

An economical inquiry into an unlikely city

A model of 3rd century Trier in the Rheinische Landesmuseum in Trier.

Abstract

|

Today Trier is a small city in the German state of Rhineland-Palantine. It lies on the Moselle river, a west tributary of the Rhine river, and is surrounded by wooded hills. But seventeen hundred years ago, in the fourth century, Trier was a very large and wealthy city. Estimates of its urban population range from 50.000 to 100.000 people. It was after Rome probably the largest city in the Western empire. It was definitely the largest city of the empire not situated on or near the coast. And this is what makes it special, because Trier had no easy access to the cheapest form of transport: seaborne trade. In this article we will take a look at some possible reasons for how such a large urban center could flourish in such an unlikely place.

|

"For maritime cities are able to bear such times of need withouth difficulty, by an exchange of their own pruducts for what is imported: but an inland city like ours can neither turn its superfluity to profit, nor supply its need, by either disposing of what we have, or importing what we have not" - Gregory of Nazianzus (Orationes 43).

introduction

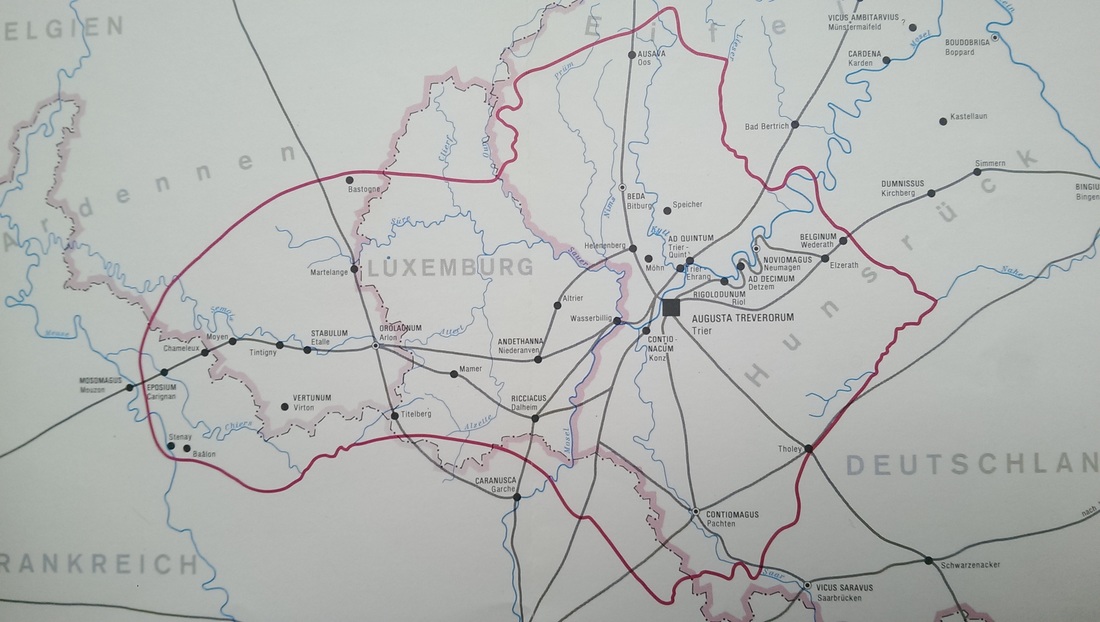

The city of Augusta Treverorum was founded around 13 BCE, in the Moselle valley between the Eifel and Hunsrück mountain ranges. The precise location, a narrow strip of river between the southbank of the river and a range of hills, was uninhabited. Other than being the capital of the civitas Treverorum (municipality of the Treveri people, in what is now Luxemburg, the French departement Moselle and the German state of Rhineland Palantine), it had no political significance in the province of Gallia Belgica. The city grew quickly, and kept growing through times of war, plague and instability. Around the middle of the second century it had a population of approximately 20.000 people and around the middle of the third century the population had grown to about 30.000. By then it had an amphitheater, a circus, at least two large bathing complexes and a 300 years old stone bridge.

And now the main question: People have to eat. Transporting food is expensive. The larger a city is, the further away its food needs to come from, but the further away it comes from, the more expensive it gets. How could a city without access to the cheap transport of maritime shipping and cut off from the well developed trade networks of the Mediterranean get so large and so wealthy?

The main problem with answering the question is that we have almost no sources aboutTrier between its founding and the third century. To overcome this obstacle there will be a heavy reliance on economical and geographical theory, combined with geographical, epigraphical and archeological evidence. In this way at least we approach a semblance of historical veracity (as long as no unknown political shenanigans were going on).

And now the main question: People have to eat. Transporting food is expensive. The larger a city is, the further away its food needs to come from, but the further away it comes from, the more expensive it gets. How could a city without access to the cheap transport of maritime shipping and cut off from the well developed trade networks of the Mediterranean get so large and so wealthy?

The main problem with answering the question is that we have almost no sources aboutTrier between its founding and the third century. To overcome this obstacle there will be a heavy reliance on economical and geographical theory, combined with geographical, epigraphical and archeological evidence. In this way at least we approach a semblance of historical veracity (as long as no unknown political shenanigans were going on).

Civitas Treverorum with the roads, rivers and the most important places. From Heinen, 1985.

Growth of a city

The economic function of a city is to be the center of a region, where local products are marketed, sometimes via smaller centers, such as villages. There is a barrier in the continued growth of a city. Urban centers have a hinterland, the area that markets its agricultural surplus in the center. This hinterland has natural boundaries, beyond which it becomes more profitable to market goods in another center. A city can only grow as large as the food production of the hinterland allows. After that point the city either stops growing or it starts importing food from beyond the borders of its hinterland. Because transport costs for bulky inexpensive goods such as food are usually quite high the import of food makes all food prices rise more. The growth-barrier is where it is no longer profitable to transport food to the city because the distance has become too great. Although this barrier can ultimately only be overcome by political intervention (like the imperial subsidizing of grain in Rome) it can be pushed somewhat up. This can be done by either making food cheaper or by raising purchasing power in the city.

The hinterland

|

"But if fortune attends our prayer, we shall have a farm in a healthful climate [...] not far from the sea or a navigable stream, by which its products may be carried off and supplies brought in" - Columella ( Res Rustica I, 2,3).

"Farms which are nearby suitable means of transporting their products to the market and convenient means of transporting thence those things needed on the farm, are for that reason profitable" - Varro (Rerum Rusticarum I, 16,3) |

Lowering prices

|

There are two ways of lowering prices: increasing supply or lowering transport costs.

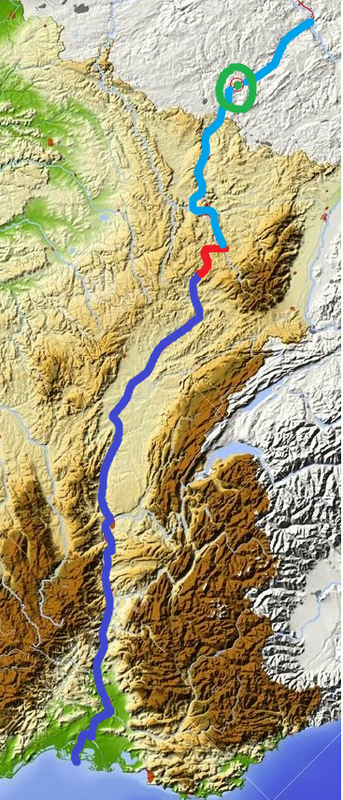

The Romans levied their taxes in general in coin. This means that subsistence farming independent from the market wasn't an option. Surpluses absolutely needed to be produced and sold on a local market, or taxes couldn't be paid. This helped to lower food prices in two ways: Firstly it means that more food will enter the market and thus come within grasp of the urban consumer. Secondly, the monetization of the economy meant that more investment went into farms, so that production rose (when you're dependent on the market anyway, why not try to make a profit next year?). Farmers did very well in Civitas Treverorum in Roman times. We know that more and more (and poorer and poorer) arable land was cultivated, and that the region was about as forested as it is now. Because they weren't centrally provisioned, the presence of the Roman armies on the Rhine created a large demand for locally produced goods like food, fabrics and leather, and Mediterranean luxury items like olive oil and wine. That demand created a trade route between the Mediterranean and North seas, via the large rivers of eastern France and western Germany. The trade route went up the Rhône until Lyons, from there up the Saône. At the watershed of Escles the trade went overland for about 50 kilometer, after which it followed the river Moselle towards the Rhine and from there on to the North Sea. Scholars agree that this was the main artery of trade in the whole of Roman France and Germany, and Trier was on it. On the trade route goods had to be transloaded a number of times. Not only between boats and carts at the Escles watershed, but also between larger and smaller vessels when rivers became smaller or shallower. Trier was one of the places where goods were transloaded from smaller vessels onto larger ones. The abovementioned tributaries of the Moselle, the Sauer, the Kyll and the Saar, were all very calm, accessible for larger boats and navigable very far upstream for smaller ones. This means that even smaller farmers living far away from Trier had the opportunity to bring their surplus to Trier via rivers. The fact that two and later three Roman roads crossed at Trier was important for the same reasons as the rivers were: they facilitate cheap transport and thus cheap food. The existence of the always hungry legions downstream of Trier also meant that the foodprices were never going to be too low; the Rhine market was just too big. Farmers never had to gamble on food prices, they knew they would make a decent profit if their products would reach the market. This also meant that a lot of food destined for the Rhineland flowed through Trier, so that its inhabitants could buy and eat what they wished. Because if food is going to be expensive, it's going to be less expensive up the Moselle in Trier than down in the Rhineland. |

The Mediterranean-North Sea route

Dark blue: Rhône and Saône Red: Land transport Light blue: Moselle Green circle: Trier |

Increasing purchasing power

|

What do you do when you want to buy more things? It's easy: you sell more things. The Roman Moselle valley is and was known for its vineyards. Romans agronomical technology was quite advanced, and already in republican times the Roman gentleman farmer had over a hundred cultivars of grape to choose from, depending on climate, soil type and altitude. The vineyards around Trier were probably part of medium estates that were managed in the northern Gallo-Roman style, where low amounts of slave labor and high amounts of seasonal hired labor were combined with a high degree of involvement by the owner and his family. We know from archaeological evidence that this way of producing was highly profitable: the villas attached to these estates where often quite luxurious. The wine made was shipped both up and down the river in large barrels. In the hills and uplands of the Ardennes, Eifel and Hunsrück a lot of sheep were herded, and their wool was bought, sold and manufactured into high quality cloth in Trier, which was then exported to both the Rhineland and the Mediterranean. The city was known for the luxury tableware it produced. There was a very large potters quarter on Trier's southern border and terra sigillata from Trier has been found in both of the Germanias as well as in all three of the Gallias. The city also had one or more prolific mosaic workshops. Trierer mosiacs have been found in the whole of Belgica.

|

Many-oarded rivership carrying barrels of wine on the Moselle. Ca 220 CE in Neumagen, Germany. Now in the Reinische Landesmuseum in Trier.

|

|

Other ways of getting more money is by getting rich people to live in your city, or making sure large amounts of money flow through your city. In Trier this happened at the same time when it became the seat of the financial procurator of Gallia Belgica and both Germanias (procurator provinciae Belgicae utriusque Germaniae). This magistrate was responsible for collecting the taxes in the three provinces. We don't know why and when Trier was chosen, but it is likely that it was because of the central place Trier occupies between the provincial capitals of the three provinces, with direct roads leading to all of them. At some point, we again do not know why or when, the capital of Gallia moved from Reims to Trier. This meant that it was now the political center of the province, that carried with it all the prestige, culture and landed elite-luring properties we expect from Roman capitals. Many of the provincial elite must have moved to the city, or at least had a city residence there. We know from archaeology that many large and luxurious mansions were built, sometimes taking up an entire block of houses (insula) in the city. These people came to spend their rural profits and rents in Trier instead of in their home cities, thus making the city richer and at the same time creating more demand for luxury products.

|

An Roman is feeding grain into a mechanical reaper, called vallus in Latin. Relief found at Buzenol, Belgium, inside the borders of Civitas Treverorum. Now in the archeological museum of Arlon.

|

Conclusion

How could a city without access to the cheap transport of maritime shipping and cut off from the well developed trade networks of the Mediterranean get so large and so wealthy? Let's keep it short and clear:

- A large and prosperous hinterland.

- Situated on a major river system for cheap trade.

- A strategic position on the major trade route between Mediterranean and the North Sea.

- The nearness of a nearly insatiable market in the Rhineland-based armies.

- A consolidation of political power in the city.

Literature

|

Links and further reading

|

Al images are taken from Wikipedia or belong in a similar public domain.

29-01-2016 KDD