POMPEII

STUDYING THE URBANISM OF POMPEII

LRA (2016)

Pompeii is probably one of the best known Roman cities thanks to its outstanding state of preservation. It presents a picture of how the citizens of almost two thousand years ago used to live. Pompeii is, however, much more than that: it gives us information about the way a city was organized, why some streets were more evidently crowded than others, which streets the traders would choose for placing their shops, and how the presence of this shops affected the flow of pedestrians. In this webpage a series of facts will be highlighted which will help address these issues.

inTRODUCTION

|

Founded as a Roman colony in 80 BC, Pompeii is one of the best conserved examples of a Roman city. This extraordinary state of preservation is due to the well-known Vesuvius’ eruption in 79 AD which covered the city under a layer of ashes, lapilli and lava, petrifying everything and everyone that had the misfortune of being there at the moment. The terrifying moments the inhabitants experienced remain captured thanks to the work of Pliny the Younger:

"I looked around: a dense black cloud was coming up behind us, spreading over the earth like a flood. ‘Let us leave the road while we can still see’, I said, ‘or we shall be knocked down and trampled underfoot in the dark by the crowd behind.’ We had scarcely sat down to rest when darkness fell, not the dark of a moonless or cloudy night, but as if the lamp had been put out in a closed room." Epist. 6.20. Pliny to Cornelius Tacitus |

On the other side, the awful event gave us historians, archaeologists or whoever interested in the study of the Ancient World, the opportunity to study a truly “snapshot“ of a port Roman town.

Although the first topic that comes up to mind when thinking about Pompeii is the image of the great wallpaintings, the petrified corpses and the large quantity of everyday objects (which of course have an archaeological and historical importance that is proportional to the fascination they produce), for understanding the daily life of a town and their activities, it is not only convenient to study the human rests, the objects found and the structure of the buildings themselves: it is also a necessity to analyse how and why the city was built the way it was, which criteria were used when placing public buildings and spaces -and what this implied-, or what made a particular street popular. Summarizing: how did a city organize its space. The combination of Ancient urbanism with the study of the modern one could be seen imprudent, but actually it is not: in van Neese’s words: “it can be said that the way a society organizes its functions spatially and the way its spatial structure affects the human behaviour, in terms of the location pattern of its activities, has not changed much in two thousand years.” (Akkelies van Nees, 2011)

As the architectural layout has been almost perfectly conserved, studying ancient urbanism based on archaeological data from the site of Pompeii is extremely useful. Although only three quarters of the territory of the city have yet been excavated, it is enough for intuiting with accuracy the rest of the urban plan. We have evidence of the location of stores, workshops, public spaces like thermae, temples, and private buildings of all kinds, from the poorest to the wealthiest. In this case, the analysis is going to be focused in the latest period of the city of Pompeii, just about the time it was covered by the ashes of Vesuvius.

Although the first topic that comes up to mind when thinking about Pompeii is the image of the great wallpaintings, the petrified corpses and the large quantity of everyday objects (which of course have an archaeological and historical importance that is proportional to the fascination they produce), for understanding the daily life of a town and their activities, it is not only convenient to study the human rests, the objects found and the structure of the buildings themselves: it is also a necessity to analyse how and why the city was built the way it was, which criteria were used when placing public buildings and spaces -and what this implied-, or what made a particular street popular. Summarizing: how did a city organize its space. The combination of Ancient urbanism with the study of the modern one could be seen imprudent, but actually it is not: in van Neese’s words: “it can be said that the way a society organizes its functions spatially and the way its spatial structure affects the human behaviour, in terms of the location pattern of its activities, has not changed much in two thousand years.” (Akkelies van Nees, 2011)

As the architectural layout has been almost perfectly conserved, studying ancient urbanism based on archaeological data from the site of Pompeii is extremely useful. Although only three quarters of the territory of the city have yet been excavated, it is enough for intuiting with accuracy the rest of the urban plan. We have evidence of the location of stores, workshops, public spaces like thermae, temples, and private buildings of all kinds, from the poorest to the wealthiest. In this case, the analysis is going to be focused in the latest period of the city of Pompeii, just about the time it was covered by the ashes of Vesuvius.

the sources

For the elaboration of this article, the simple but deep analysis of a detailed Pompeii map was unavoidable (one of the most useful tools for this matter is the Google Map developed by Pompeionline.net, - Google Map of Pompeii- , the official webpage of the archaeological site). Some websites, especially the above-mentioned (www.pompeionline.net) and some others contain trustworthy information about the site, the history and provides some graphic material. These electronic tools help students and researchers to receive interactive information that would be difficult to get through the traditional means, and makes the process of studying much more interesting and productive. Nevertheless, the work of Akkelies van Nes, Eric E. Poehler and others in the volume Rome, Ostia, Pompeii. Movement and space” (2011) has been significantly important, as well as Pompeii and Herculaneum by A. Cooley and M. Cooley among others.

What makes a street popular?

Picture 2

Picture 2

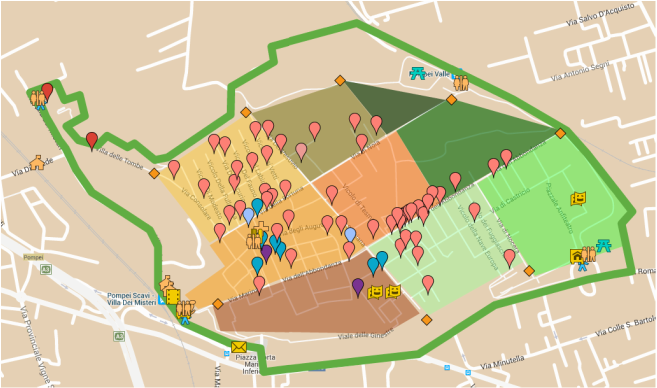

The relationships goes both ways: the way the city organizes its activities affects the architectural organization of the city, the same way the existence of certain structures in an area is used in favour of economic and social activities. Normally, the main streets (the two principal perpendicular streets from which every other street begins, the so-called cardo maximus and cardo decumanus, are the ones that get more affluence, due to several reasons. One of this are the most straight streets: the more changes of direction, the more segregated a street will be (in Picture 2, depicts a map with the most popular streets of Pompeii highlighted). From these streets, an orthogonal grid plan would be developed for the construction of the rest of the streets and neighbourhoods. The urban building expansion took place for the most part along Via dell'Abbondanza, a symbolic centre of the new emerging class. (Pompeionline.net, 2016) The Via di Nola and Via Stabiana had also great importance.

Besides, these streets also have in common the high level of visibility from other streets. The most popular streets have the biggest number of entrances to it, and the more number of parallel entrances which offer visibility from other streets and roads, which creates the effect of more amplitude, making the experience of the pedestrians more agreeable. These characteristics are not a conditio sine qua non, as there is evidence of popular streets with a very low entrance density, but a lot of connections to important streets, or streets with few connections to other streets but high visibility. Picture 3 shows a map of Pompeii and its principal amenities (offices, Fora, thermae, temples, dwellings, offices, etc). It is noticeable that they tend to be located around the most popular streets.

However, a city is, and was back then, a dynamic organism: the places once crowded can become abandoned in a couple of generations, new constructions replace the old buildings, and urban planning is more and more developed to get the most intelligent and comfortable structure to the city.

Contrary to what one might think, the location of the public buildings does not necessarily have to do with the attendance of people there. This explains, for example, why the Forum Civile (and some other public amenities, like the Temple of Vespasian or the Temple of Jupiter), despite being places specifically made for the influx of citizens, are not integrated within the most popular streets: they actually were in the past, but the increasingly growth of the population made re-organization of the city indispensable, being substitute by the new principal streets, straight and wide, capable of receive an each-year bigger number of pedestrians.

Besides, these streets also have in common the high level of visibility from other streets. The most popular streets have the biggest number of entrances to it, and the more number of parallel entrances which offer visibility from other streets and roads, which creates the effect of more amplitude, making the experience of the pedestrians more agreeable. These characteristics are not a conditio sine qua non, as there is evidence of popular streets with a very low entrance density, but a lot of connections to important streets, or streets with few connections to other streets but high visibility. Picture 3 shows a map of Pompeii and its principal amenities (offices, Fora, thermae, temples, dwellings, offices, etc). It is noticeable that they tend to be located around the most popular streets.

However, a city is, and was back then, a dynamic organism: the places once crowded can become abandoned in a couple of generations, new constructions replace the old buildings, and urban planning is more and more developed to get the most intelligent and comfortable structure to the city.

Contrary to what one might think, the location of the public buildings does not necessarily have to do with the attendance of people there. This explains, for example, why the Forum Civile (and some other public amenities, like the Temple of Vespasian or the Temple of Jupiter), despite being places specifically made for the influx of citizens, are not integrated within the most popular streets: they actually were in the past, but the increasingly growth of the population made re-organization of the city indispensable, being substitute by the new principal streets, straight and wide, capable of receive an each-year bigger number of pedestrians.

conclusions

Through this brief research, it can be concluded that:

- Pompeii, being a wealthy Roman port city, is an excellent source for studying many aspects of the Roman world, one of which is urbanism.

- The traders or craftsmen tend to place their shops in the most popular streets.

- A street's popularity can change with the passage of time.

- The streets are more or less popular depending on several factors, such as straightness, visibility, connection with other important streets and the presence of shops, but neither of these factors is determinant or essential by itself.

- The presence of public amenities (even if they are specifically made for the attendance of citizens) does not necessarily make a street popular.

bibliography and references

- Beard, M. (2008). "Pompeii : the life of a Roman town." London.

- Cooley, A. and Cooley, M. (2014). "Pompeii and Herculaneum." Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Laurence, R., Newsome, D. J., et all. (2011) "Rome, Ostia, Pompeii. Movement and Space". Oxford University Press.

- MacDonald, W.L. (1986) The architecture of the Roman Empire. II. An urban appraisal, "Yale publications in the History of Art 35", New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Milnor, K. (2014). "Graffiti & the literary landscape in Roman Pompeii." Oxford University Press.

- Özgenel, L. (2008) “A tale of two cities: in search for ancient Pompeii and Herculaneum”, METU JFA 2008/1.

- Rowland, I. (2014). "From Pompeii. The afterlife of a Roman town" Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Webpages

- Pompeionline.net, P. (2016). Pompeii Map by Pompeionline.net. [online] Google.com. Available at: https://www.google.com/maps/d/viewer?mid=zF0D46fy4BJI.ko54lE5Q7IL0 [Accessed 28 Jan. 2016]. (Google Maps of Pompeii)

- Cartwright, M., Cartwright, M. and Cartwright, M. (2016). Pompeii. [online] Ancient History Encyclopedia. Available at: http://www.ancient.eu/pompeii/ [Accessed 28 Jan. 2016].

- Pompeionline.net, (2016). Pompeii Ruins - History. [online] Available at: http://www.pompeionline.net/pompeii/history.htm [Accessed 28 Jan. 2016].

Picture references

- Banner: http://www.dayofarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/DSC_4048.jpg

- Picture 1: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6b/Italy_provincial_location_map.svg/800px-Italy_provincial_location_map.svg.png

- Pictures 2 and 3: https://www.google.com/maps/d/viewer?mid=zF0D46fy4BJI.ko54lE5Q7IL0