Tarraco

Hot, rich and dear to Augustus

Tarraco was a city in the northeast of Spain which gained political influence, splendour and beauty after the visit of emperor Augustus in 29 BC. The city received political favors, as Augustus had a special connection with Tarraco, including a new building program. The emperor improved the Via Heraclea and changed the name to Via Augusta. Years later, an altar to Augustus and to Roma was set up. After Augustus’ death the Tarragonan people – with permission of the new emperor Tiberius – built a temple to Augustus, which was the signal for the new provincial cult. Later on a certain Lucius sponsored by testament an arch to Augustus. The coins struck in Tarraco show us images of Augustus, but also tell us something about the constructions mentioned above.

By K.J. (28-01-2016)

THE ETERNAL LIFE OF EMPEROR AUGUSTUS

After its prominent role in the second Punic war (218-201 BC), the Hispanian city of Tarraco became - quite suddenly - important in the first years of the rulership of emperor Augustus. In a war with the Cantabri in the north of Hispania Augustus became sick and decided to leave the battlefield in 25 BC. He headed to Tarraco, a city in the north-east of Hispania that was seen as the capital city of the later Roman province Hispania Tarraconensis. [1] This visit was the only way in which the name of Augustus would be remembered in this city. How did the city of Tarraco immortalize emperor Augustus?

political changes

Somewhere between 45 and 27 BC the city of Tarraco received the title Colonia Iulia Urbs Triumphalis Tarraco. [2] The word Triumphalis refers to the victory of Iulius Caesar over Hispania in 49 BC. Years later, probably in 27 BC [3], the emperor Augustus instituted provincial reforms which also affected Hispania Ulterior and Hispania Citerior. These reforms were mainly administrative and they rearranged the Iberian peninsula into the provinces Baetica, Lusitania and Tarraconensis. One of them was the entry of the system of conventus: areas that function as a place where people could gather to practice justice and to conclude civil business. [4] Augustus made Tarraco – being such a special city – the capital city of the Conventus Tarraconensis as well as the capital city of the province Tarraconensis, which became the biggest one of the Roman Empire. As a consequence it adopted a plan to fit its new status as a juridical and administrative centre in the west. [5]

Fig.1: Left: Hispania in 56BC, Right: Hispania in 10AD. Tarraconensis is displayed in green.

Constructions

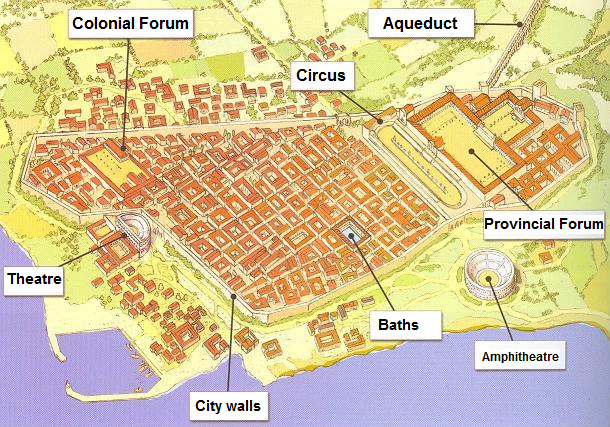

For Tarraco the influence of Augustus was not just political. His being shaped part of the city plan (Fig.2). The theatre in the southwest was built around the first visit of Augustus in 26 BC as part of the decoration program in the whole empire. Probably found on the provincial Forum was the Augustan basilica of Tarraco, which also had the aedes Augusti. [6] Close to this was the Via Augusta, which was crossed by the Arch of Bèra (situated outside the plan below). Another important monument is the temple of Augustus that was to be found on the Colonial Forum. The location of the Altar of Augustus is not known.

|

Fig. 2: Map of late-Roman Tarraco. The aqueduct and circus are built in the late 1st century AD, the amphitheatre in the early 2nd century, the baths in the late 2nd or early 3rd century.

|

AltarThat the inhabitants of Tarraco were supporters of emperor Augustus was clear; they even set up a provincial cult in which they worshipped him. [7] No archaeological evidence of this altar is found; however, other sources assume its existence. On the coins of Tarraco we find a depiction of it (Fig.6: no.3) and in the writings of Quintilian the altar is also recalled. [8] In this last source, however, it is mentioned quite ironically, as the text refers to the altar as almost unused. The altar as well as the temple show the loyalty of the elite or other certain groups in Tarraco to the imperor. [9]

About the location of the altar nothing is known, but the local scale of the activities that took place around it suggest that it was situated on the provincial forum in the south of the city. [10] Other altars built in the Augustan era – the altar of the three Gauls in Lugdunum (Lyon), the Ara Ubiorum in Oppidum Ubiorum (Cologne) and the altar to Augustus in Emerita Augusta (Mérida) – are quite different from the one in Tarraco. In Tarraco the installation of the imperial cult, which accompanied the erection of the altar, went very slow, while at the other altars the imperial cult came together with reorganization of the provinces. [11] |

Via augustaBetween 16 and 13 BC Augustus went to Spain again. When he noticed the bad shape the roads were in, he gave orders to upgrade them. His army restored the former Via Heraclea that then changed name and became the Via Augusta. Starting at Narbo it went through the Pyrenees along the coast to Tarraco, which was a major city on the road. Tarraco gained lots of commercial advantages by its position. [12] Together with its location at sea and status as capital city the wealth of Tarraco was tremendous.

|

Fig.3: no.1: the Via Augusta (red) in modern Spain, no.2: the Via Augusta (grey) in Tarraco.

|

|

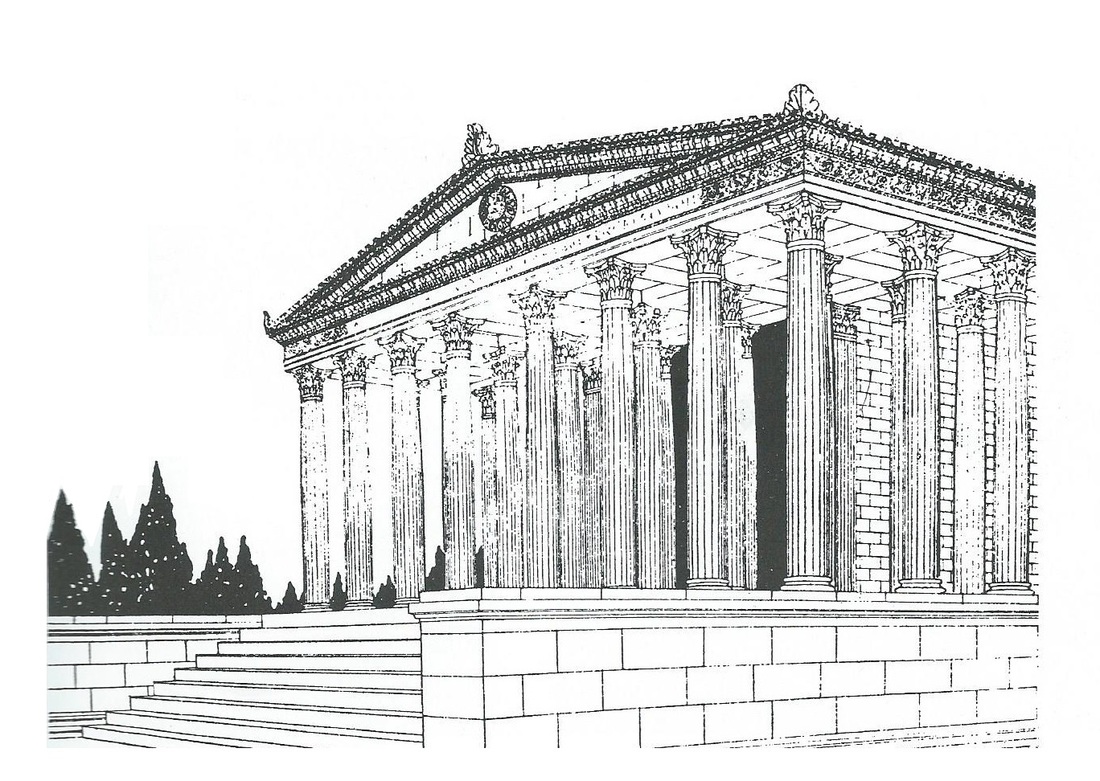

Fig.4: Reconstruction of the temple to Augustus in Tarraco.

|

TempleAfter his death in 14 CE Augustus was quite soon declared divus. The people of Hispania immediately reacted on this by requesting the new emperor Tiberius that a temple to Augustus should be built in the city of Tarraco. [13] In the northeast of the town a temple to Augustus was erected. The style of the building was typical for the Julio-Claudian time, as coins showing the temple demonstrate (Fig.6: no.1/2). These coins are undoubtedly struck in remembrance of the temple; they normally have the text AETERNITAS AVGVSTAE. [14]

Not only did the Tarragonan people display their Roman identity with this provincial cult, but it also expressed their loyalty to the empire. By this Tarraco distinguished itself from other, ‘minor’ cities in the network of Rome. [15] According to Tacitus, Tarraco was the first city in a row that expressed that it wanted to construct a temple to Augustus. However, evidence is found that in the province of Lusitania, which is situated next to Tarraconensis, a similar temple existed. With the altar and this temple the provincial cult is instituted in this province. Keep in mind that there were more temples in Tarraco, for example the temple of Juppiter Ammon. [16] |

archAbout twenty-two kilometres to the north-east of the city centre is the location of an arch, the Arch of Bèra, which crosses the Via Augusta. Lucius Licinius Sura sponsored this honorific arch by testament. [17] He was praefectus of the Hispanian city of Celsa, but migrated to the more important city of Tarraco during the reign of Augustus. Besides the dedication to the emperor, this monument was a piece of euergetism intending to monumentalize the Tarragonan coastal area. A more recent interpretation of the Arch of Bèra says that it is a territorial arch which is situated on the place where the Via Augusta leaves the territory of Tarraco and enters that of Barcino. [18]

|

Fig.5: The Arch of Bèra, formerly crossed by the Via Augusta.

|

Coins

As already said, there are some coins found on which either the Augustan temple or the altar of Tarraco is shown. On the front side of these dupondii a portrait of emperor Augustus is to be seen. On the first one (Fig.6: no.1) a ’common’ imperial portrait of Augustus is to be seen, along with the text DIVVS AVGVSTVS PATER. Another coin (Fig.6: no.2) shows a more peculiar figure: Augustus is sitting on a throne while holding a globe in his right hand, topped by a winged Victoria. [19] At the same time he puts one of his hands in the air. This whole image looks exactly like the mighty Zeus Olympios by the sculptor Phidias. It is quite normal that an deified emperor is portrayed with attributes of an Olympian or Roman god. [20] The text around this figure is DEO AVGVSTO, which is remarkable as one would expect divo. The terminology for honouring a deified ruler is not set, so this text is not necessarily excessive adulation. [21] On the last coin (Fig.6: no.3) we can see the head of emperor Augustus again, along with the same text. All the coins above are struck in Tarraco under the reign of emperor Tiberius (14-37).

|

|

|

Fig.6: Three combinations of coins.

|

Conclusion

The analysis given above makes clear that there were three ways in which the city of Tarraco immortalized the emperor Augustus. Firstly by using the political importance given by the emperor itself; secondly by remembering him in constructions and coins; thirdly by honouring him in constructions and coins, too. Tarraco made herself special by being more important than other cities, doing it in another way or excelling in it.

Notes |

|

References |

Text

[1] Alföldy (1991): 20. [2] Alföldy (1991): 35-6. [3] Dio Cassius LIII, 12. [4] Pliny, Naturalis Historia III, 18. [5] Dupré i Raventós (1995): 361. [6] For the basilica of Tarraco, see: Trillmich & Zanker (1990): 155-7. [7] For the provincial cult in Hispania and the worship of Divus Augustus, see: Fishwick (1987): 154-163. [8] Quintilian, de Institutio Oratoria VI, 3, 77. [9] Trillmich & Zanker (1990): 157. [10] Trillmich & Zanker (1990): 158. [11] Trillmich & Zanker (1990): 158. See also for more information about the other altars. [12] Carreté, Keay & Millett (1995): 33. [13] Tacitus Annales I, 78. [14] For discussion about the meaning of these words, see Fishwick (1987): 151-2. [15] Barclay (2011): 346-50. [16] Florus 2,9. [17] RIT 930. [18] Dupré i Raventós (1995): 359. [19] For the meanings of Victoria, see: Fishwick (1987): 115-8. [20] Barclay (2011): 351. [21] Fishwick (1987): 151-2. Figures Cover photo: http://www.mby.com/cruising/top-10-catalonia-cruising-grounds-marinas-anchorages-47064/2 Fig.1: http://explorethemed.com/iberiarome.asp?c=1 Fig.2: adapted from http://blogs.sapiens.cat/historiadorvital/2013/03/28/quan-tarraco-va-ser-la-capital-de-limperi-roma/ Fig.3 (no.1): http://www.eyeonspain.com/blogs/bestofspain/11954/Tour-Spain-along-the-Roman-roads.aspx Fig.3 (no.2): http://www.wikiwand.com/en/Tarraco Fig.4: Fishwick (1987): plate XXX. Fig.5: http://www.mnat.cat/?page=arcbera-gal-imatges Fig.6 (no.1/2): Fishwick (1987): plate XXVII a/c. Fig.6 (no.3): Fishwick (1987): plate XXXVII b. |