Leptis Magna and the emperor septimius severus

Summary

The ancient city of Leptis Magna had a special relationship with its former resident, Julius Septimius Severus, ruler of the Roman Empire in the years 193-211. This webpage deals with the issue of the impact that having a resident who became emperor had on the appearance of this originally Phoenician city. When studying public buildings, erected during the imperial period, one discovers a peak in construction activities during the reign of the Septimius. Severus. The Phoenician factor, till then visible in this Romanized city, disappeared and an Oriental element was introduced, initiated by S. Severus.

It is hard to say what happened in the period following the reign of S. Severus. A decline in construction is likely, although construction may have continued in the suburbs of the city. However, since these areas have not been excavated, this remains uncertain.

The ancient city of Leptis Magna had a special relationship with its former resident, Julius Septimius Severus, ruler of the Roman Empire in the years 193-211. This webpage deals with the issue of the impact that having a resident who became emperor had on the appearance of this originally Phoenician city. When studying public buildings, erected during the imperial period, one discovers a peak in construction activities during the reign of the Septimius. Severus. The Phoenician factor, till then visible in this Romanized city, disappeared and an Oriental element was introduced, initiated by S. Severus.

It is hard to say what happened in the period following the reign of S. Severus. A decline in construction is likely, although construction may have continued in the suburbs of the city. However, since these areas have not been excavated, this remains uncertain.

Introduction

Leptis Magna was a city, located in the desert of North-Africa and therefore ‘a city in the sand’. Yet Leptis Magna was described as “Glistening in marbles, a brilliant Roman town reflecting its glory in the green-blue waters of the Mediterranean. …rays of sunrise and sunset have loaned colors of false fire to its walls. Greatness and beauty were here”. (Matthews, 1957)

After reading this, of course one wants to know more about this beautiful city. This document is a first step in introducing the city and its famous resident, Lucius Septimius Severus, who became ruler of the Roman Empire (193-211).

This weebly aims to find an answer to the following question: did the fact that S. Severus, son of the city, became emperor influence the appearance of Leptis Magna? And if so, in what way? In what follows first a short historical view on Leptis Magna and S.Severus is presented, then the appearance of the city before, during and after the reign of S. Severus is described. This research will be limited in time and concerning structures; only the Imperial Period and only public buildings will be discussed. As investigation is limited, the conclusion cannot be considered definitive and comprehensive but merely as an interesting idea.

Leptis Magna was a city, located in the desert of North-Africa and therefore ‘a city in the sand’. Yet Leptis Magna was described as “Glistening in marbles, a brilliant Roman town reflecting its glory in the green-blue waters of the Mediterranean. …rays of sunrise and sunset have loaned colors of false fire to its walls. Greatness and beauty were here”. (Matthews, 1957)

After reading this, of course one wants to know more about this beautiful city. This document is a first step in introducing the city and its famous resident, Lucius Septimius Severus, who became ruler of the Roman Empire (193-211).

This weebly aims to find an answer to the following question: did the fact that S. Severus, son of the city, became emperor influence the appearance of Leptis Magna? And if so, in what way? In what follows first a short historical view on Leptis Magna and S.Severus is presented, then the appearance of the city before, during and after the reign of S. Severus is described. This research will be limited in time and concerning structures; only the Imperial Period and only public buildings will be discussed. As investigation is limited, the conclusion cannot be considered definitive and comprehensive but merely as an interesting idea.

|

History Leptis Magna was founded by Phoenicians at the end of the 6th century BC. The city is located at the mouth of the Wadi Lebdah on the coast of the Mediterranean. In the Punic Wars the city was allied with Carthage and therefore came under Roman control after the Roman victory. In 8 BC the town was declared an emporium. Not surprisingly because due to its natural harbor Leptis Magna had always been an important link between the Trans-Savannah-caravans and the Mediterranean partners. Yet trade was not the main cause for wealth, agriculture brought a lot more. Although lying in a dry region Leptis Magna had a fairly good rainfall, the warmth and water enabled the production of wheat and olive-trees. Agriculture and trade together had generated an incredible wealth for the city. |

Under Vespasian (69-79) the city was made a municipium, which entailed certain Roman rights and privileges. Trajan (98-117) granted Leptis Magna colonial rights in 109 AD, which meant Roman citizenship to all residents and the adoption of Roman titles and hierarchy.

S. Severus, finally, gave the city the Ius Italicum in 203 AD, which brought freedom of taxes. During the general decline of the Roman Empire trade decreased dramatically but Leptis Magna remained wealthy; the olive-oil production still flourished and this saved the city for a while.

In 455 AD Vandals took over the city; from then on the decline set in. Leptis Magna suffered attacks of Berber tribes, an earthquake, flooding, the Byzantine takeover and lastly the Arabs captured the city. Because of the wars between the Muslims and the rest of Europa, trade of olive-oil was no longer possible and this meant the melt-down of Leptis Magna.

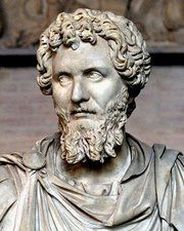

In the 2nd century AD, the heyday of the city, S. Severus ascended to the imperial throne. He was born in Leptis Magna and his family belonged to the local elite. He climbed up through the ranks of Romans and became - backed by his army - emperor of Rome, in 193 AD. In 203 AD he visited his native town.

S. Severus, finally, gave the city the Ius Italicum in 203 AD, which brought freedom of taxes. During the general decline of the Roman Empire trade decreased dramatically but Leptis Magna remained wealthy; the olive-oil production still flourished and this saved the city for a while.

In 455 AD Vandals took over the city; from then on the decline set in. Leptis Magna suffered attacks of Berber tribes, an earthquake, flooding, the Byzantine takeover and lastly the Arabs captured the city. Because of the wars between the Muslims and the rest of Europa, trade of olive-oil was no longer possible and this meant the melt-down of Leptis Magna.

In the 2nd century AD, the heyday of the city, S. Severus ascended to the imperial throne. He was born in Leptis Magna and his family belonged to the local elite. He climbed up through the ranks of Romans and became - backed by his army - emperor of Rome, in 193 AD. In 203 AD he visited his native town.

ill. 3 Leptis Magna

ill. 3 Leptis Magna

Leptis Magna before S. Severus

If one would know whether the emperor S. Severus, had some impact on the appearance of Leptis Magna, we first have explore the city in the time of the early empire before the reign of S. Severus.

At that time many Roman buildings were erected in Leptis Magna. In 56 AD Nero built (ill. 3 section 1) in an old quarry, the amphitheatre, next to the Circus, which was built a century earlier. Near the sea and the harbor (section 3) the Forum was constructed with the Curia, Basilica and several Temples, dedicated to Roman gods. Section 4 finally shows again typical Roman structures like a Theatre, Markets; the Punic-Roman market and an indoor-market, and the Temple for the Imperial Family.

At the north bank of the river (section 4 top left) Hadrian provided the Thermae. And almost all the emperors had their own triumphal Arch in the city. So Romanization was clearly visible in the Julio-Claudian Period. In the 2nd century the city was embellished; buildings were redecorated and the brown limestone was replaced with marble.

Our conclusion is that at the end of the 2nd century Leptis Magna was one of the finest and most Romanized cities of North- Africa. Though, here a note should be made to the concept of Romanization.

If one would know whether the emperor S. Severus, had some impact on the appearance of Leptis Magna, we first have explore the city in the time of the early empire before the reign of S. Severus.

At that time many Roman buildings were erected in Leptis Magna. In 56 AD Nero built (ill. 3 section 1) in an old quarry, the amphitheatre, next to the Circus, which was built a century earlier. Near the sea and the harbor (section 3) the Forum was constructed with the Curia, Basilica and several Temples, dedicated to Roman gods. Section 4 finally shows again typical Roman structures like a Theatre, Markets; the Punic-Roman market and an indoor-market, and the Temple for the Imperial Family.

At the north bank of the river (section 4 top left) Hadrian provided the Thermae. And almost all the emperors had their own triumphal Arch in the city. So Romanization was clearly visible in the Julio-Claudian Period. In the 2nd century the city was embellished; buildings were redecorated and the brown limestone was replaced with marble.

Our conclusion is that at the end of the 2nd century Leptis Magna was one of the finest and most Romanized cities of North- Africa. Though, here a note should be made to the concept of Romanization.

Romanization with Phoenician elements

For sure Leptis Magna was a Romanized town. But beneath the superficial veneer of Roman culture existed a strong Phoenician

(i.e. Punic) element. Despite Roman rule and dominance, the city was home mostly to natives of Phoenician or Libyan background and during the 1st and 2nd century AD they retained their Punic legal and cultural traditions. Residents continued to use their own Punic coinage, names, titles and language.

For sure Leptis Magna was a Romanized town. But beneath the superficial veneer of Roman culture existed a strong Phoenician

(i.e. Punic) element. Despite Roman rule and dominance, the city was home mostly to natives of Phoenician or Libyan background and during the 1st and 2nd century AD they retained their Punic legal and cultural traditions. Residents continued to use their own Punic coinage, names, titles and language.

|

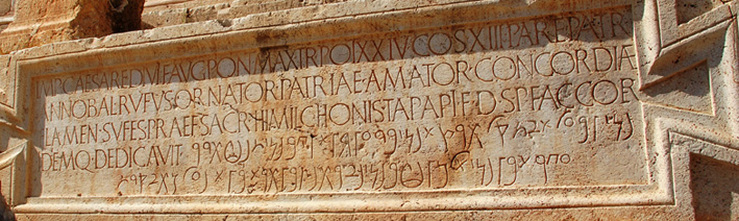

Evidence of this is e.g.

a bilingual inscription (ill. 4) from the 2nd century AD. The text is Latin-Punic, the name of the citizen, Annobal Tapapius Rufus is a Punic-Latin combination and the Punic title 'flamen', mentioned in the inscription, has a Latin equivalent; a local priest. |

|

The Phoenician factor is also visible in architecture. Reliefs about human origin

and growth were different from Roman art. (ill. 5) and the Phoenicians had phallic images placed on lintels and door-entrances for warding off the evil. (ill. 6) The street pattern did not show, as most Roman cities do, the tight Hippodamian grid and although Romans used to place the Forum on the intersection of the Cardo and Decumanus, the inhabitants of Leptis Magna put their Forum near the harbor. The conclusion is that there was Romanization, but that the city also had definite Phoenician chracteristics. |

Leptis Magna during the reign of S. Severus

Now we have to look at what happened to the shape of the city under the reign of S. Severus. With his ascent to the imperial throne, an ambitious building-program was rolled out. S. Severus has redecorated and embellished nearly all Roman facilities mentioned before and the list of newly erected structures is impressive. Only a few Severan constructions are discussed below.

S. Severus expanded the harbor (ill. 3 section 1) with various port-facilities: porticos, warehouses, a lighthouse at the north jetty,

on city-side new quays, a temple and altars. He enlarged the basin and constructed a dam; an artificial channel and reservoirs were built in order to prevent flooding and silting. On the west bank of the river (ill. 3 section 3) S. Severus created his own monumental plaza including a

Forum, Nymphaeum, Temples for the Gens Septimia and Concordia and the huge Basilica. Moreover he built the Colonnaded Street running from this monument-place to the harbor. Finally, in the center of Leptis Magna (ill. 3 section 4) the emperor placed his Quadrifons, a richly decorated, four-sided Arch.

All in all, a massive quantity of Roman structures and again with a special Phoenician/Oriental touch.

Now we have to look at what happened to the shape of the city under the reign of S. Severus. With his ascent to the imperial throne, an ambitious building-program was rolled out. S. Severus has redecorated and embellished nearly all Roman facilities mentioned before and the list of newly erected structures is impressive. Only a few Severan constructions are discussed below.

S. Severus expanded the harbor (ill. 3 section 1) with various port-facilities: porticos, warehouses, a lighthouse at the north jetty,

on city-side new quays, a temple and altars. He enlarged the basin and constructed a dam; an artificial channel and reservoirs were built in order to prevent flooding and silting. On the west bank of the river (ill. 3 section 3) S. Severus created his own monumental plaza including a

Forum, Nymphaeum, Temples for the Gens Septimia and Concordia and the huge Basilica. Moreover he built the Colonnaded Street running from this monument-place to the harbor. Finally, in the center of Leptis Magna (ill. 3 section 4) the emperor placed his Quadrifons, a richly decorated, four-sided Arch.

All in all, a massive quantity of Roman structures and again with a special Phoenician/Oriental touch.

Oriental elements

Just as in the 1st and 2nd century AD a Phoenician element was noticeable in the Romanized architecture, in Severus’ time an Oriental influence was visible. For the large amount of building-activities many skilled architects from Greece, Asia-Minor and the East were sent in. And their special Oriental-Mediterranean style is clearly present in Leptis Magna of Severus’ days. The short pedestals of the columns, the row of Medusa’s guarding the Forum (ill. 7) and the cut pediment with parts pulled apart on the Quadrifrons (ill. 8) are typical examples of Roman buildings, devised by Asian architects.

We can conclude that under rule of S. Severus there was an outburst of construction-activities and the Oriental architects and

artisans left their mark on the city-buildings.

Just as in the 1st and 2nd century AD a Phoenician element was noticeable in the Romanized architecture, in Severus’ time an Oriental influence was visible. For the large amount of building-activities many skilled architects from Greece, Asia-Minor and the East were sent in. And their special Oriental-Mediterranean style is clearly present in Leptis Magna of Severus’ days. The short pedestals of the columns, the row of Medusa’s guarding the Forum (ill. 7) and the cut pediment with parts pulled apart on the Quadrifrons (ill. 8) are typical examples of Roman buildings, devised by Asian architects.

We can conclude that under rule of S. Severus there was an outburst of construction-activities and the Oriental architects and

artisans left their mark on the city-buildings.

Leptis Magna after S.Severus

When checking the appearance of Leptis Magna immediately after the reign of S.Severus, a decline in urban investment and embellishment can be observed. Caracalla (211 AD) finished the last large building, the Hunting Baths, while the following emperors of the 3rd and 4th century AD only made modest additions and small improvements. Reasons for this stabilization are maybe enemy-attacks, the silting of the harbor followed by diminishing trade, and in general the crisis of the Roman Empire. There also was a tendency to build in the countryside that has not yet been excavated.

For now we can conclude that, based on archaeological knowledge, in the time after S. Severus virtually no construction-activities were undertaken. Only minor ornamentation and repairs were done.

Conclusion

Apparently the appearance of Leptis Magna is influenced because the city had a resident who became emperor. Leptis Magna was already a beautiful city in marble with an original Phoenician factor before S. Severus became emperor. In Severus’ days the construction and redecoration of public utilities and spaces in an architecture with an Oriental element, was overwhelming compared with the period before and after his reign.

When checking the appearance of Leptis Magna immediately after the reign of S.Severus, a decline in urban investment and embellishment can be observed. Caracalla (211 AD) finished the last large building, the Hunting Baths, while the following emperors of the 3rd and 4th century AD only made modest additions and small improvements. Reasons for this stabilization are maybe enemy-attacks, the silting of the harbor followed by diminishing trade, and in general the crisis of the Roman Empire. There also was a tendency to build in the countryside that has not yet been excavated.

For now we can conclude that, based on archaeological knowledge, in the time after S. Severus virtually no construction-activities were undertaken. Only minor ornamentation and repairs were done.

Conclusion

Apparently the appearance of Leptis Magna is influenced because the city had a resident who became emperor. Leptis Magna was already a beautiful city in marble with an original Phoenician factor before S. Severus became emperor. In Severus’ days the construction and redecoration of public utilities and spaces in an architecture with an Oriental element, was overwhelming compared with the period before and after his reign.

Literature

Cordovana , Orietta D., 'Between History and Myth: Septimius Severus and Leptis Magna', Greece & Rome 59.1 (2012) 56-75.

Matthews, Kenneth D. Jr., Cities in the sand. Leptis Magna and Sabratha in Roman Africa. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1957).

Pollard, Nigel, 'Leptis Magna Splendour and Beauty in North Africa' in: John Julius Norwich (ed.), Cities that shaped the Ancient World.

(London: Thames & Hudson Ltd., 2014) 104-109.

Klein, Fred S., A History of Roman Art. (International/Enhanced edition; Boston, Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2010).

Images

1 http://www.asa-agency.com/media/4a9b9f24-b71a-11e2-8bef-3bf5702a1822

2,3 http://www.rizzuti.org/Libia/LeptisMagna/LeptisMagna_en.htm

4 http://lila.sns.it/mnamon/index.php?page=Esempi&id=23&PHPSESSID=fpxoeogttmuhz&lang=en

5,6 http://www.wondermondo.com/Countries/Af/Libya/Murqub/LeptisMagna.htm

7 http://historiesofthingstocome.blogspot.nl/2011/06/ancient-cities-3-leptis-magna.html

8 http://romeartlover.tripod.com/Leptis1.html

9 http://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-roman-emperor-septimius-severus-lucius-septimius-severus-augustus-64924928.html

NHCRdJ

Cordovana , Orietta D., 'Between History and Myth: Septimius Severus and Leptis Magna', Greece & Rome 59.1 (2012) 56-75.

Matthews, Kenneth D. Jr., Cities in the sand. Leptis Magna and Sabratha in Roman Africa. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1957).

Pollard, Nigel, 'Leptis Magna Splendour and Beauty in North Africa' in: John Julius Norwich (ed.), Cities that shaped the Ancient World.

(London: Thames & Hudson Ltd., 2014) 104-109.

Klein, Fred S., A History of Roman Art. (International/Enhanced edition; Boston, Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2010).

Images

1 http://www.asa-agency.com/media/4a9b9f24-b71a-11e2-8bef-3bf5702a1822

2,3 http://www.rizzuti.org/Libia/LeptisMagna/LeptisMagna_en.htm

4 http://lila.sns.it/mnamon/index.php?page=Esempi&id=23&PHPSESSID=fpxoeogttmuhz&lang=en

5,6 http://www.wondermondo.com/Countries/Af/Libya/Murqub/LeptisMagna.htm

7 http://historiesofthingstocome.blogspot.nl/2011/06/ancient-cities-3-leptis-magna.html

8 http://romeartlover.tripod.com/Leptis1.html

9 http://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-roman-emperor-septimius-severus-lucius-septimius-severus-augustus-64924928.html

NHCRdJ