THE ASKLEPIEIon

OF KOS

(1) The Asklepieion of Kos.

|

(2) The Island of Kos, with the city in the north.

|

aBSTRACTThis short study looks at the influence the Asklepieion at Kos had on the city and its inhabitants. In order to do so, the topics of physicians (doctors), pilgrimage, and the Asklepios festival (Asklepieia) will be examined. Each of these topics sheds light on different aspects of the common identity of the inhabitants of Kos displayed at the Asklepieion. The research shows that these elements culminated at the Asklepieion to show a common identity that was expressed in a number of different ways.

|

Introduction |

The polis of Kos was positioned under Ptolemaean influence during most of the Hellenistic period. Despite this 'subordination', there is an abundance of evidence to show that there was autonomous government on Kos and, as Carlsson[1] argues, the assumption that Kos did indeed remain for all practical purposes an autonomous democracy is well-founded in the evidence. What differentiates this form of democracy from the Athenian archetypical democracy is the arguable[2] introduction of demagogues from the elite classes on Kos. These elite citizens needed to secure favour among the common people in order to maintain their position of influence within this democratic system.

|

Van Nijf[3] proposes an interesting way of looking at public events: he states that elite citizens could generate favour by participating in and organising games. Doing either (or both) would add to their prestige and give in turn a boost to their political careers. The important aspect of this is of course the provision of entertainment for the people and the show of excellence, in Van Nijf's research illustrated by the victory of games by such a prominent citizen. In the polis of Kos, a very specific kind of excellence was attested and widely valued: the art of medicine. Doctors belonged to the highest social class on Kos[4] and would therefore have a likelihood of starting a political career. I will argue that we can see the presence of doctors in the highest classes of society on Kos reflected in one very specific area of Kos: the Asklepieion. A sanctuary to Asklepios, the god of medicine, the Asklepieion provides a perfect opportunity to study its relevance to Kos, a city renowned for its many medical professionals. Since we know that decrees by the government and commemorations were set up at the Asklepieion[5], I hypothesise that the Asklepieion was one of the centers of Koan profilation, both by citizens and by the city as a whole.

|

Since Kos was known throughout the Greek world for its doctors, we will first look at them. A doctor could be recruited both inside and outside the island of Kos, via one of two ways: either a city asked for medical assistance and the council of Kos decided on a doctor, or a city asked for a specific doctor and this doctor would then go there.[6] The second way is interesting, since it shows that doctors, much like athletes, became famous when they had performed well in previous jobs. This fame could be and was exploited by Kos to gain prestige. This can be seen in a number of inscriptions that have been found, which commemorate the help a Koan doctor provided to another city.

|

Physicians |

An interesting example of the honours bestowed on a doctor for services delivered can be seen in an inscription of the 2nd century BC for the doctor Kallippos. He was awarded a golden crown, a payment of 300 staters, and he was given a dispatch to secure publication at the Asklepieion of the honours bestowed.[7] The fact that the community of Aptera gave such honours was interesting, since they have tended to reserve giving them only to the most prominent persons (i.e. military generals, kings, etc.).[8] These honours were therefore likely regarded highly and their publication on the Asklepieion granted extra prestige to the site and the city.

Pilgrimage(1) First platform of the Asklepieion of Kos.

|

Another way in which Kos attracted positive recognition for itself was via pilgrimage[9]. The Asklepieion, located just a few kilometers outside the city, was a destination for Greek citizens in the vicinity of Kos. Here they hoped to receive godly intervention that would cure their diseases. The procedure was as follows: a sick person would come to the Asklepieion, pray to Asklepios, and sleep in an incubation chamber. Then, hopefully, Asklepios would appear in his dream (in some form) and would cure his disease.[10] If they were cured, the ill would often leave a votive offering to commemorate the healing. In addition, the cult of Asklepios itself would publicise recoveries, known as iamata, and keep those as a kind of proof of success in the sanctuary.[11] These votive offerings, which sadly are not readily accessible, and the registers for successful divine treatments serve as a reminder of the healing of the god and would by association reflect positively on Kos.

|

|

The Asklepieion was constructed in the 3rd century BC and was finished somewhere before 242 BC. The area, however, was in use as a sacred area since the second half of the 4th century BC and has been linked to the foundation of the new city of Kos in 366 BC at its current location in the north. Most likely the sanctuary was constructed as a direct consequence of the settlement in this new location.[12] It is important to note this, since the construction of the Asklepieion is therefore most likely done not only for religious purposes, but also for political purposes.

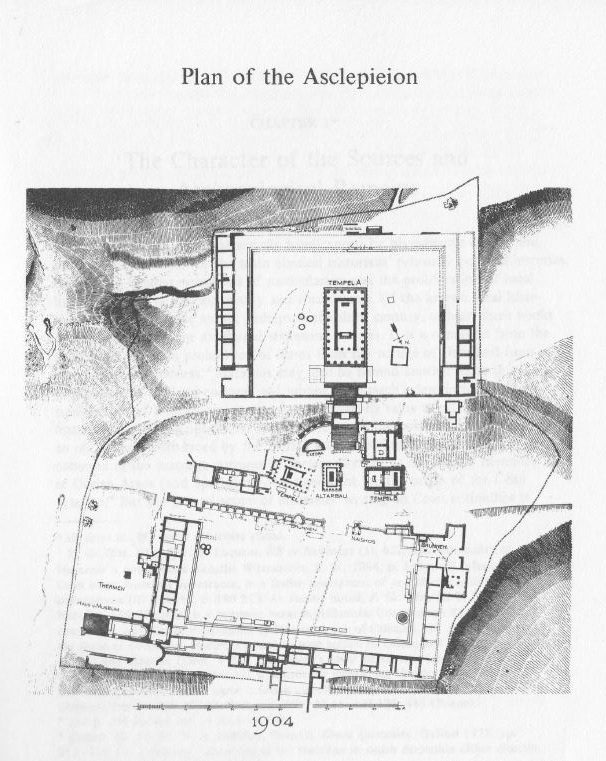

In order to get a good appreciation of the value of the Asklepieion, it is important to take a moment to describe the complex. When approaching the complex, one was confronted with a high wall and central staircase, and this view continued on the first and second platform. This centrality of the staircases (see figure (1), see above) gave a certain axiality to the complex, endowing it with a sense of grandeur.[13] For the entire layout, please refer to figure (5) below for a plan of the complex. The high walls, made even larger by the buildings constructed on top of them, gave an added sense of magnificence to the construction which served to elevate its greatness even further. Additionally, looking out from the second or third platform, a visitor could see the sea and the neighbouring islands. This, I claim, added a sense of elevation, both literal and figurative. |

The Asklepieion and the Asklepios festival |

|

(5) Plan of the Asklepieion.

|

Kos hosted an annual festival, known as the Asklepieia, which also knew a penteteric and pan-Hellenic version known as the Great Asklepieia. The festival hosted two important features of a festival: games and a sacrifice to Asklepios. The games, as Van Nijf has shown[3], were a venue for prominent citizens to prove both their benefaction and their excellence. The sacrifice, on the other hand, contained a special element: a procession from the city to the Asklepieion.[14] This aspect deserves special attention, since it is of major importance. Remember the visual value of the Asklepieion: its grandeur was probably large enough to awe the people in the procession. The people in the procession, consisting of both Koan and extra-insular visitors, would be influenced by these sights and would in addition be confronted with a number of inscriptions and statues detailing not only decrees but also honors given to local doctors by other cities, and benefactors of Kos. The Asklepieia, then, gave an opportunity for the city and its prominent citizens to present themselves: the prominent citizens could show their greatness either by benefaction for the festival or by success in the games, while the city at large could show the achievement of its citizens via the inscriptions and, of course, via the accomplishments of its prominent citizens.

|

In conclusion |

The Asklepieion was the place where a number of characteristic activities with respect to Kos came together. Pilgrimage, the provision of doctors to foreign cities and the festivities of the Asklepieia all contributed in their own way to the positive image of the city of Kos and provided a positive image towards the people of Kos as well. The comparability of the medical profession with the Asklepieion (specifically Asklepios' healing) gave a compelling reason to publicise the honorary decrees for doctors on the Asklepieion, as this would give a perfect opportunity to promote Kos as a center of healing. A regular citizen could take pride in the greatness of his city, and an elite citizen used his wealth to perform benefaction and through this benefaction raise his standing among fellow citizens. The exposure of the city and the proliferation of the aforementioned positive image allowed for the Koan people as a whole to experience a shared identity of magnificence and to really feel that their city was beautiful.

|

Notes

[1] Carlsson (2000), Höghammar (ed.), 109-118.

[2] Of course, the Athenian democracy had known famous demagogues as well. The importance and multitude of such characters, however, largely increased during Hellenistic times, as Carlsson shows.

[3] Van Nijf (2011), 47-95.

[4] Sherwin-White (1978), 270-271.

[5] Carlsson (2010), 240.

[6] Sherwin-White (1978), 264-268.

[7] Sherwin-White (1978), 267.

[8] Inscriptiones Creticae II, iii-3. The relevant section is found in lines 12-18, where Kallippos is bestowed a golden wreath and 300 staters in compensation. Lines 27-31 show that the people of Aptera gave an honorary stele, to be placed on the Asklepieion.

[9] It should be noted that pilgrimage is defined here as 'going to a sanctuary of a god'. This can be for any reason: a journey out of piety or a journey in order to request something from a god. In this short study, the second case is most prominent and is therefore the focus of the research into this topic. Pilgrimage in this case is therefore connected specifically to requesting treatment from Asklepios.

[10] Dillon (1997), 74-80.

[11] Sherwin-White (1978), 349-350.

[12] Sherwin-White (1978), 340.

[13] Hollinshead (2012), 41-46.

[14] Sherwin-White (1978), 356-359.

Bibliography

Carlsson, S. (2010). Hellenistic Democracies: Freedom, Independence and Political Procedure in some East Greek City-States. Stuttgart: Steiner.

Dillon, M. (1997). Pilgrims and pilgrimage in ancient Greece. London: Routledge.

Höghammar, K. (2000). 'The Hellenistic polis of Kos: state, economy and culture.' Proceedings of an international seminar organized by the Department of Archaeology and Ancient History. Uppsala: Dept. of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University.

Hollinshead, M. B. (2012). Architecture of the Sacred: Space, Ritual and Experience from Classical Greece to Byzantium. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sherwin-White, S. M. (1978). Ancient Cos: an historical study from the Dorian settlement to the imperial period. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.

Van Nijf, O. M. (2011). 'Political Games'. Entretiens sur l'Antiquité Classique Tome LVIII: L'Organisation des Spectacles dans le Monde Romain. Genève: Fondation Hardt Vandoeuvres, 47-95.

Images

(1) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kos#/media/File:Kos_Asklepeion.jpg

(2) http://imgcon.com/371254-kos-island-greece-map.html

(3) Own image

(4) Own image

(5) Sherwin-White (1978), 11.

This page was written by: S. B. (28-01-2016)