Ephesos,

benefaction and civic identity

AbstractThe foundation of Salutaris is a significant and exemplary source which tells us how public munifence by a wealthy member of the ruling elite influenced the civic identity of Ephesos. The inscription tells us about lotteries and distributions financed by Salutaris and how they show the ideal hierarchy of the city according to the elite. The procession, made possible through the dedication of images by Salutaris, shows us how the young, future elite men of the city were acculturated by participating in a ritual which focused on the historical, mythical and religious background of the city, but also on the position of the city in the Roman Empire.

|

Ephesos, munificence, social control and identityMost people know Ephesos as the location where the temple of Artemis, one of the ancient seven world wonders, was located. However, there are much more interesting things to tell about this city from Asia-Minor. Extensive archeological and historical work has been done to find out more about this fascinating polis (city) and the world it was situated in. It would be too big of a subject to cram the whole history of this polis[1] in one small page so the thing we will take a closer look at is in what ways euergetism[2] (from the ancient greek word for benefactor, euergetes) or public munificence has contributed to a common identity in Ephesos. Euergetism was a way for the polis to create stability in a time of growing disparity and oligarchisation of polis politics. This munificence from the elite manifested itself primarily in financing processions, festivals, public building or just a money handout. The benefactor could get privileges, public honours like statues, monuments and decrees written by the city council in return.

|

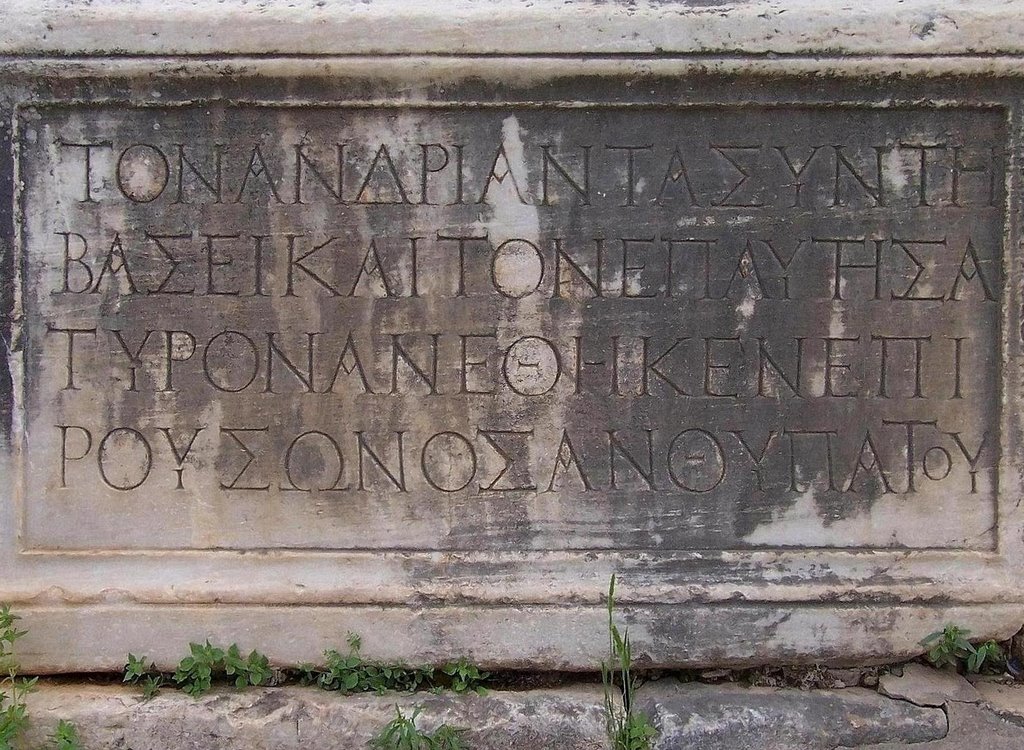

Ephesos Curetes Street, example of a votive inscription on a pedestal.

|

OUr source: The Salutaris Foundation

There are dozens of sources available to demonstrate this, but we will focus on an exemplary inscription from a benefactor named Salutaris. The foundation is from 104 AD and made possible by Salutaris, who was born a Roman citizen and a member of the equestrian order. Even before this benefaction, he was a citizen of Ephesos and a member of the city council. Salutaris chose to show his munificence not by financing a new public building, but by creating a lottery and a procession.[3]

The inscription was inscribed on a wall of the south entrance of the theatre. The text itself would have been pretty difficult to read for passersby. The letters were to small and the inscription itself too high for easy reading. Apparently, the exact details weren’t important enough to let everybody read it every time they walked past. It was probably more a symbol of his generosity, having an inscription in such prominent and publicly important place. The realization of this inscription was a legal process which symbolized and legitimized the power relationships of the city, province and empire. It was a two way street, not an instrument of oppression. Members of the elite like Salutaris who wanted to make such a benefaction first had to negotiate with the non-council citizens about terms; they couldn’t simply put it up and dismiss the people’s wishes.

The inscription was inscribed on a wall of the south entrance of the theatre. The text itself would have been pretty difficult to read for passersby. The letters were to small and the inscription itself too high for easy reading. Apparently, the exact details weren’t important enough to let everybody read it every time they walked past. It was probably more a symbol of his generosity, having an inscription in such prominent and publicly important place. The realization of this inscription was a legal process which symbolized and legitimized the power relationships of the city, province and empire. It was a two way street, not an instrument of oppression. Members of the elite like Salutaris who wanted to make such a benefaction first had to negotiate with the non-council citizens about terms; they couldn’t simply put it up and dismiss the people’s wishes.

lotteries and distributions

One way in which the Salutaris inscription shows us how identity was formed through munificence is the hierarchy of the recipients of his lotteries and distributions. When you look at the percentages of received gifts you notice that the members of the tribes were the highest in the civic hierarchy in Ephesos, which was a group of around 1500 citizens. This refers to the foundation story of the city; these tribes were the original settlers from Athens who followed the advice of the oracle. So not only does it have a historical background, but also a divine one. After them came the wealthy and prominent men of the city council and the gerousia (council of elders). The ephebes (adolescent men) also formed an important part of the civic hierarchy, but this may be more a way of acculturation in order to make sure that the young men knew their future place and identity in the city and how the political hierarchy came to be. However, certain groups were also omitted. For example, the guilds and other groups weren't mentioned at all, while they were very important for the wealth of the Ephesos. This may have been a clear message from the Ephesian aristocracy: Keep your place, outside politics.

The Procession

|

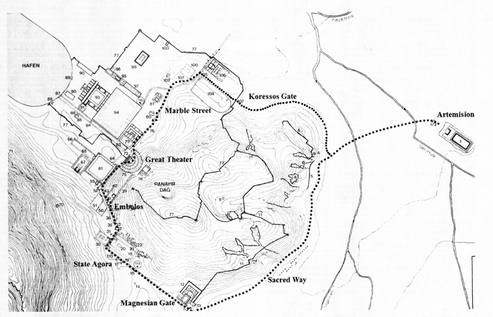

The procession can also inform us about identity through euergetism. Salutaris conceived this procession and the demos approved it. He also promised to dedicate twenty-nine images according to the decree. The ephebes were the group responsible for receiving and escorting the procession, which, like at the lotteries and distributions, was probably a way to acculturate them, giving them responsibilities and letting them walk past the important parts of the city, which were connected to the history of the city. Statues and images they carried were also a part of the identity of Ephesos. The goddess Artemis was present, but also other important figures like Androklos, who was the founder of the city and images of the five original tribes, all important in the foundation story of the city. The information we have about the weight of the images is one way the civic hierarchy is presented. The statues of Artemis were the biggest or covered with gold and the other images were smaller, according to its importance and made of silver. The Romans were also prominent in the procession. Images of the current emperor Trajan and his wife Plotina, as well as of Augustus, the Senate and the Roman people were carried along. This clearly shows the attempts of the Ephesians to incorporate them in their worldview, besides showing respect to the Roman emperor and Rome.

|

To conclude

We have seen how the Salutaris inscription can inform us about the way public benefaction works. The procession, lotteries and distributions show us that the ruling elite tried to promote their ideal city hierarchy and identity by focusing on the religious, historical and mythical background of Ephesos, to acculturate the future generation of elites, and to incorporate Rome and the Roman emperor into the worldview and identity of the citizens of Ephesos.

S.K.

S.K.

References

1)For an introduction to the history and findings of Ephesos: Peter Scherrer, Ephesus: The new guide (Turkije: Ege Yayınları, 2000).

2)For a detailed description and some case studies on euergetisme in Asia-Minor: Arjan Zuiderhoek, The politics of Munificence in the Roman Empire: citizens, elites and benefactors in Asia minor (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

3)For the Greek text and the English translation: Guy Maclean Rogers, The sacred identity of Ephesos : foundation myths of a Roman city (London en New York: Routledge, 1991), 153-18.

2)For a detailed description and some case studies on euergetisme in Asia-Minor: Arjan Zuiderhoek, The politics of Munificence in the Roman Empire: citizens, elites and benefactors in Asia minor (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

3)For the Greek text and the English translation: Guy Maclean Rogers, The sacred identity of Ephesos : foundation myths of a Roman city (London en New York: Routledge, 1991), 153-18.

FURTHER READING

-Parrish, David; Abbasoğlu, Halûk. Urbanism in Western Asia Minor : new studies on Aphrodisias, Ephesos, Hierapolis, Pergamon, Perge, and Xanthos. Portsmouth: Journal of Roman Archaeology, 2001.

-Koester, Helmut. Ephesos, Metropolis of Asia: an interdisciplinary approach to its archaeology, religion, and culture. Distributed by Harvard University Press for Harvard Theological Studies/Harvard Divinity School, 2004.

-Koester, Helmut. Ephesos, Metropolis of Asia: an interdisciplinary approach to its archaeology, religion, and culture. Distributed by Harvard University Press for Harvard Theological Studies/Harvard Divinity School, 2004.