The San Vitale:

Early christian architecture

Typical Byzantine architecture or Ravannate Architecture?The city of Ravenna has a long history as a capital. At the time when Ravenna became an imperial residence under emperor Justinian I (527-565), the city underwent a true transformation. The transformation had already started before Justinian’ rule, but was continued during his rule party because of his political and religious agenda. Over the years building programs were established through which the prestige of the city significantly increased. Today these buildings are an important source for our understanding of early Christian art and architecture because of a lack of surviving literary sources. An important building in Ravenna is the church of San Vitale. The church shows an incredible artistic skill, including a blend of Greco-Roman traditions, Christian iconography and oriental and western styles. But can this mix of architectural styles be identified as typical Byzantine architecture or as typical Ravannate architecture?

|

In the fifth and sixth century, Ravenna was one of the most important and influential cities in the Mediterranean.[1] The city experienced a development in art and architecture. The San Vitale and its mosaics are the result of this flourishing development and show a high level of material prosperity. It is also a sign of the competitive building programs of churches in Ravenna in the fifth and sixth centuries.[2] Under the reign of emperor Justinian I this flourishing development continued and he even supported the building programs and requested for buildings and churches. An important reason for Justinian’s interest in building churches is his goal to unify Christianity in his empire. He thought that different sorts of Christian beliefs made the chance of disloyalty higher. Many local lords or local Christian rulers followed the example of Justinian to gain his favour, like the archbishop of Ravenna named Maximianus (546-556). Maximian had a great influence on the appearance of the San Vitale. The construction of this church begun under Bishop Ecclesius (522-532) and was completed and consecrated under Maximian. The construction of the San Vitale took place under the episcopate of no less than four bishops and under two different political and religious regimes, namely the Arian Ostrogoths and the Orthodox Byzantines. The San Vitale was commissioned under the rule of Ostrogothic ruler Theoderic and after the Gothic Wars continued under the reign of Justinian. The church is often praised for its impressive and different appearance.

To determine in which arthistorical at context the San Vitale should be placed, the church has often been analyzed. An arthistorical method that is often applied to monuments of Ravenna, and in this case at the San Vitale, is called ‘formalism’. With this method stylistic characteristics which do not seem typical for their time and place are being compared with possible equivalent stylistic features of other buildings and places. When the material is identified the stylistic features are ascribed to the arrival of foreign designers, promoting a theological or liturgical renewal, a political principle or to the taste and influence of a local ruler. This kind of analysis can provide new interpretations of art and architecture, a new and broader context of the church or for new insights into cultural exchanges.[3] With this analysis is to conclude that the function of the buildings and its characteristics in Ravenna are not comparable to a single tradition and therefore Ravenna is an amalgamation of various influences.

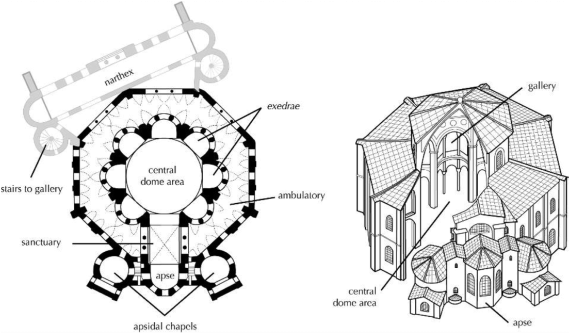

But is, as the conclusion after the formalism suggests, the San Vitale a typical building of Ravannate architecture? The San Vitale is characterized by its octagonal floorplan, the arches resting on eight pillars and connected by niches. The double octagonal floorplan with a gallery, which is unique to Ravenna, is a local variation of the architecture in the eastern capital Constantinople. The floorplan of the San Vitale looks similar to the St. Sergious and Bakchos, which was completed in 536 long before the San Vitale was finished.[4] So the San Vitale has been influenced by external influences. The center of the church is surrounded by seven niches which contain the gallery and is covered by a dome. The dome only covers the inner octagon. The ambulatory has been covered by its own roof. The apse is located in the eighth niche. It contains the famous imperial panels of the emperor Justinian I and his wife Theodora. Due to the niches around the center of the church and their verticality a new unity in the design of the construction was developed. Also the order of the semicircular niches produces a new unity of design. The impression of unity is supported by the proportions of the church.[5] In front of the church was located a narthex. The narthex touched only one of the eight corners of the octagon floorplan and was connected to the ambulatory by triangular portals.[6] It is unknown why the narthex was placed in this unusual way.

Ravenna’s architecture and mosaics surpasses those of any other city while the political and cultural ties between Ravenna and Constantinople and the east meant that Ravennate artists and architects were influenced by a wide range of styles.[7] The complexity of the structure of the San Vitale makes the church the product of innovation and experimentation. Due to the good climate of innovation, progress was possible in architecture under the reign of Justinian.[8] In fact, the church offers a good impression of early christian churches. The reason the San Vitale is such a good example is because it has been spared from alterations.[9] A possible reason for that is the political, cultural and economic downfall of Ravenna that started from the seventh century.

The San Vitale is not just an example of early Christian architecture but also an example of the wide range of styles combined in one building. It is a mix that consists partly of oriental influences and partly by western influences. An element that should not be forgotten is the influence of religious architecture in the San Vitale. This fusion of different influences, which all have their own characteristics, made the different architecture and local style of Ravenna possible. Thus, the San Vitale is an Ravennate example of early Christian architecture.

To determine in which arthistorical at context the San Vitale should be placed, the church has often been analyzed. An arthistorical method that is often applied to monuments of Ravenna, and in this case at the San Vitale, is called ‘formalism’. With this method stylistic characteristics which do not seem typical for their time and place are being compared with possible equivalent stylistic features of other buildings and places. When the material is identified the stylistic features are ascribed to the arrival of foreign designers, promoting a theological or liturgical renewal, a political principle or to the taste and influence of a local ruler. This kind of analysis can provide new interpretations of art and architecture, a new and broader context of the church or for new insights into cultural exchanges.[3] With this analysis is to conclude that the function of the buildings and its characteristics in Ravenna are not comparable to a single tradition and therefore Ravenna is an amalgamation of various influences.

But is, as the conclusion after the formalism suggests, the San Vitale a typical building of Ravannate architecture? The San Vitale is characterized by its octagonal floorplan, the arches resting on eight pillars and connected by niches. The double octagonal floorplan with a gallery, which is unique to Ravenna, is a local variation of the architecture in the eastern capital Constantinople. The floorplan of the San Vitale looks similar to the St. Sergious and Bakchos, which was completed in 536 long before the San Vitale was finished.[4] So the San Vitale has been influenced by external influences. The center of the church is surrounded by seven niches which contain the gallery and is covered by a dome. The dome only covers the inner octagon. The ambulatory has been covered by its own roof. The apse is located in the eighth niche. It contains the famous imperial panels of the emperor Justinian I and his wife Theodora. Due to the niches around the center of the church and their verticality a new unity in the design of the construction was developed. Also the order of the semicircular niches produces a new unity of design. The impression of unity is supported by the proportions of the church.[5] In front of the church was located a narthex. The narthex touched only one of the eight corners of the octagon floorplan and was connected to the ambulatory by triangular portals.[6] It is unknown why the narthex was placed in this unusual way.

Ravenna’s architecture and mosaics surpasses those of any other city while the political and cultural ties between Ravenna and Constantinople and the east meant that Ravennate artists and architects were influenced by a wide range of styles.[7] The complexity of the structure of the San Vitale makes the church the product of innovation and experimentation. Due to the good climate of innovation, progress was possible in architecture under the reign of Justinian.[8] In fact, the church offers a good impression of early christian churches. The reason the San Vitale is such a good example is because it has been spared from alterations.[9] A possible reason for that is the political, cultural and economic downfall of Ravenna that started from the seventh century.

The San Vitale is not just an example of early Christian architecture but also an example of the wide range of styles combined in one building. It is a mix that consists partly of oriental influences and partly by western influences. An element that should not be forgotten is the influence of religious architecture in the San Vitale. This fusion of different influences, which all have their own characteristics, made the different architecture and local style of Ravenna possible. Thus, the San Vitale is an Ravennate example of early Christian architecture.

Notes

[1] Deborah Mauskopf Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 1-3.

[2] Kenneth G. Holum, “The classical city in the sixth century,” in The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian, ed. Michael Maas. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005): 99.

[3] Deliyannis, 16.

[4] Mariëtte Verhoeven, The Early Christian Monuments of Ravenna: Transformations and Memory (Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2011), 129

[5] Richard Krautheimer, The Pelican History of Art: Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Inc, 1975), 244-249.

[6] Verhoeven, 46.

[7] Deliyannis, 15-16.

[8] Massimiliano David, Eternal Ravenna: from the Etruscans tot he Venetians (Turnhout: Brepols Publisher, 2013), 139.

[9] Otto Mazal, Justinian I. und seine Zeit: Geschichte und Kultur des byzantinischen Reiches im 6. Jahrhundert (Keulen: Böhlau, 2001), 557-558.

[1] Deborah Mauskopf Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 1-3.

[2] Kenneth G. Holum, “The classical city in the sixth century,” in The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian, ed. Michael Maas. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005): 99.

[3] Deliyannis, 16.

[4] Mariëtte Verhoeven, The Early Christian Monuments of Ravenna: Transformations and Memory (Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2011), 129

[5] Richard Krautheimer, The Pelican History of Art: Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Inc, 1975), 244-249.

[6] Verhoeven, 46.

[7] Deliyannis, 15-16.

[8] Massimiliano David, Eternal Ravenna: from the Etruscans tot he Venetians (Turnhout: Brepols Publisher, 2013), 139.

[9] Otto Mazal, Justinian I. und seine Zeit: Geschichte und Kultur des byzantinischen Reiches im 6. Jahrhundert (Keulen: Böhlau, 2001), 557-558.

Bibliography

David, Massimiliano. Eternal Ravenna: from the Etruscans tot he Venetians. Turnhout: Brepols Publisher, 2013.

Deliyannis, Deborah Mauskopf. Ravenna in Late Antiquity. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Holum, Kenneth G. “The classical city in the sixth century,” in The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian, ed. Michael Maas. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Krautheimer, Richard. The Pelican History of Art: Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Inc, 1975.

Mazal, Otto. Justinian I. und seine Zeit: Geschichte und Kultur des byzantinischen Reiches im 6. Jahrhundert. Keulen: Böhlau, 2001.

Verhoeven, Mariëtte. The Early Christian Monuments of Ravenna: Transformations and Memory. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2011.

David, Massimiliano. Eternal Ravenna: from the Etruscans tot he Venetians. Turnhout: Brepols Publisher, 2013.

Deliyannis, Deborah Mauskopf. Ravenna in Late Antiquity. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Holum, Kenneth G. “The classical city in the sixth century,” in The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian, ed. Michael Maas. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Krautheimer, Richard. The Pelican History of Art: Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Inc, 1975.

Mazal, Otto. Justinian I. und seine Zeit: Geschichte und Kultur des byzantinischen Reiches im 6. Jahrhundert. Keulen: Böhlau, 2001.

Verhoeven, Mariëtte. The Early Christian Monuments of Ravenna: Transformations and Memory. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2011.

Images

San Vitale (header): http://hdrcreme.com/photos/7577

Plan San Vitale: https://www.studyblue.com/notes/note/n/art-history-test-3/deck/4457993

Exterior San Vitale 1: http://www.heritage-route.eu/en/ravenna/places/#.VqvE-PnhChc

Exterior San Vitale 2: http://velvetescape.com/2013/07/ravenna-attractions/

Niches inneroctagon: http://www.paradoxplace.com/Perspectives/Venice%20&%20N%20Italy/Ravenna/San%20Vitale.htm

Apse: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vitale_di_Milano

Imperial panel Justinian: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basilica_of_San_Vitale

Imperial panel Theodora: http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2012/byzantium-and-islam/blog/topical-essays/posts/san-vitale

San Vitale (header): http://hdrcreme.com/photos/7577

Plan San Vitale: https://www.studyblue.com/notes/note/n/art-history-test-3/deck/4457993

Exterior San Vitale 1: http://www.heritage-route.eu/en/ravenna/places/#.VqvE-PnhChc

Exterior San Vitale 2: http://velvetescape.com/2013/07/ravenna-attractions/

Niches inneroctagon: http://www.paradoxplace.com/Perspectives/Venice%20&%20N%20Italy/Ravenna/San%20Vitale.htm

Apse: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vitale_di_Milano

Imperial panel Justinian: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basilica_of_San_Vitale

Imperial panel Theodora: http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2012/byzantium-and-islam/blog/topical-essays/posts/san-vitale