hierapolis

|

Around two years ago several news sites dedicated an article to the discovery of the Gate to Hell.[1] Together with his team, excavator Frencesco D’Andria discovered a cave in the city center of the ancient Hierapolis, ‘sacred city.’ Remarkably enough, the team was without doubt that this must have been the gate they had been looking for when birds died instantly upon approaching it.[2] Rumors of this anti-ornithological cave structure go back to the first century BC and guided these recent excavations. Strabo, a Greek geographer from the second half of the first century, wrote about this ‘gateway to hell’ and called it a Plutonium, ‘place to Pluto.’[3] He described the Plutonium as follows:

“…while the Plutonium, below a small brow of the mountainous country that lies above it, is an opening of only moderate size, large enough to admit a man, but it reaches a considerable depth, and it is enclosed by a quadrilateral handrail, about half a plethrum in circumference, and this space is full of a vapour so misty and dense that one can scarcely see the ground.”[4] Strabo seems to have inspected the cave in detail. He describes the exterior of the cave and the rituals that took place around his time, as well.[5] The Plutonium must therefore have attracted the attention then as well as it did for d’Andria and his team now. But why did this particular cave spark the imagination of the ancient Greeks? What importance did this Plutonium play within the city causing them, for example, to build a handrail in front of the cave? When looking at the landscape and trying to establish the meaning of it for the city, I will work within the theoretical framework of “ancient memory.”[6] This framework presumes difficulty in looking at literary and epigraphic evidence by itself[7] when reconstructing memory and thus wants to connect these to the landscape and to monuments as they are built to “provoke memories.”[8] These elements combined help with the possible “memories we can detect.”[9] My research question, then, will thus be: how can the meaning of the natural landscape, the Plutonium specifically, by the Hierapolitans be deducted within “ancient memory”? |

gateway

|

|

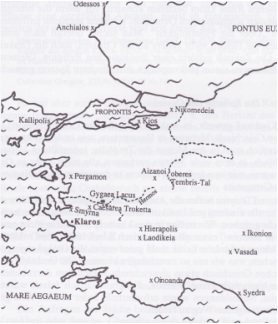

In order to answer this question I shall first give a short overview of the location of the city and its landscape. Hierapolis is located in modern Turkey. In ancient times the western part of Turkey was known as Anatolia. Hierapolis lies in the Anatolian Lycus Valley on a limestone plateau that is surrounded by the volcanic mountain Kadmos in the southeast and in the south by the mountain Salbakos.[10] The proximity of volcanic activity must have undoubtedly played a large part in the formation of the toxic gasses erupting from the cave. Besides the gasses, thermal water was to be found in the cave and on the surface of the city there were and still are thermal springs.[11]

With this image of the natural landscape in mind, the question that follows is: what did the Plutonium mean to the Hierapolitans? |

landscape

|

|

The gasses must have led the Greeks to believe that the cave formed an entrance to the underworld, or at least that it was in some way related to their myths to do with the underworld, seeing how they named it the “place to Pluto.” Several archaeological finds support this interpretation. An inscription, a statue of snakes, a statue of Pluto and a probable statue of Kore have been found[12] and supposedly rituals and sacrifices took place in the area in honor of the gods of the underworld.[13] Besides the veneration of Pluto, Apollo seemed to have been of great importance. A statue of Apollo has been found[14], and more importantly, foundations of a temple to Apollo from the third century AD with inscriptions of oracles from Apollo[15] built into its masonry.[16]

|

pluto and apollo |

|

Five kinds of oracles have been identified in these foundations.[17] However, there are two oracles on which I would like to focus as they will help sharpen our understanding of the religious memory of the landscape. The first one is an alphabetical oracle where every line of the oracle begins with a different letter of the Greek alphabet.[18] When consultation was needed a letter would be drawn randomly and then the verse starting with the same letter would be the oracle given.[19] Oracles of this kind seem to have been part of an older, ancient tradition[20] kept alive by the ancient Greeks. This specific type of oracle was uttered by the god Apollo Kareios[21],”a local form of Apollo, known both from Hierapolis itself and from Mt Tmolus in Lydia.”[22] Apparently, alphabetical oracles were not very common and “actually peculiar to a rather narrow area of western Anatolia.”[23] In other words, Apollo Kareios had been and still was an important god to the Hierapolitans in specific.

|

apollo kareios

|

|

However, this was not the only form of Apollo the inhabitants worshipped. This is where the second oracle that I would like to treat comes in. The second oracle speaks of the earth punishing the land by disease for which the only solution seems to do the following:

“sacrificing first to Gaia, … then sacrifice to Deo and the lower gods, … and pour to the heroes and chthonic gods libations … and care throughout for Apollo Kareios. For your race is from me and from city-holding Mopsos. At every gate build a sacred shrine of Clarian Phoebus … But after they have performed the propitiation and the Kares have gone far away, I order singers … to go to Colophon…” [24] Apollo Kareios we have seen, but Apollo Klarios is new. This deity provided the citizens with the second oracle and was considered to be of more importance and was venerated throughout western Asia.[25] His sanctuary was to be found in Claros, a sanctuary close by Colophon[26] that Apollo Klarios sent the Hierapolitans off to in the oracle. It is argued that this oracle does originate from Claros with the intent to “set up a religious relationship with Hierapolis” as Hierapolis shared oracular importance.[27] |

apollo klarios |

|

The apparent relationship of the Plutonium with two gods is rather intriguing. Hierapolis is not the only place to feature a Plutonium. Acharaca ,for example, featured one that does seem to have been connected to just Pluto, as a sanctuary dedicated to Pluto and an inscription in which Clodia Cognita is praised for her votive offerings to Pluto and Kore indicate. [28] The Plutonium of Hierapolis apparently differed in the way as two different deities used it. How can the concept of “social memory” help interpret the inclusion of Apollo at the Plutonium?[29]

Suggestions have been made to make sense of the name Kaireos. Two options have been given: the first one to reduce Kareios to “κάρ(α), ‘top, vertex’” and the second to “the Kares/Keres, demons or ghosts of the underworld.”[30] This underworld component would complement the Plutonium. However, due to “conical stones consecrated to Apollo … and also to the gylloi sacred to Hecate” and a difference in syllable length between the two forms, Kares seems to be disregarded as an option.[31] Accordingly it is assumed that Apollo Kareios cannot be connected to the Plutonium.[32] This I do not wholly agree with. If the name Kareios indeed derives from κάρ(α), which has a connection to both Apollo and Hecate, the role of Hecate in communication between worlds should not be forgotten. Therefore I would suggest to not excluding a possible connection just yet. Of course, the precise meaning of the Plutonium is difficult to reconstruct based only on spelling in inscriptions, as “ancient memory” may be involved.[33] However, I would like to provide two other, tangible sources[34] that might help reconstruct the way in which the Hierapolitans wished to remember the Plutonium based upon the aspects that citizens considered important enough for conservation,[35] one epigraphical and the other archaeological. One, the oracle of Claros speaks of an angry, chthonic earth that has to be conciliated which could be interpreted as a reference to the chthonic Plutonium.[36] Moreover, due to coins that show Apollo and a deity of the underworld on the same coin (figures 5 and 6), for example Apollo and the rape of Persephone,[37] it would seem that Apollo and Pluto were both a part of the Plutonoium as the coins display usage of the Plutonium for both oracular facilities (Apollo) and otherworldly connections (Persephone). |

shared plutonium

|

|

Surely the cave caught the attention of the Hellenistic Greeks (and Romans afterward). Because of the carbon dioxide and animals dying from it, the cave was considered to be connected to the underworld. Due to the same gasses the cave must have similarly been ascribed a prophetic function explaining the veneration of Apollo. This means that the landscape itself created the possibility for religious expression, but the inhabitants adapted it for multiple uses that fit their needs. Accordingly they put tangible monumental structures on the site, thereby creating additional emphasis on the special character of the cave, from which ancient memory could possibly be deducted. However, ‘just’ a monument was not enough as foundations of the monument prove to be another source for memory as the uttered oracles have been inscribed and correspondingly incorporated in the building. These oracles referred to the religious traditions of the city with Apollo Kareios and his alphabetical oracles. They furthermore showed the importance of Hierapolis as a religious site, seeing how Claros is thought to have wanted to connect with Hierapolis. Lastly, the oracles traced the history of the city back to foundation origins and this in combination with the temple opposite the Plutonium could be interpreted in a way that Hierapolis was and wanted to show that the city was truly an important and ancient holy site to be reckoned with.

|

conclusion

|

|

[1] E.g.: R. Lorenzi. “Pluto’s Gate Uncovered in Turkey.” Discovery News. Published March 29, 2013. http://news.discovery.com/history/archaeology/gate-to-hell-found-in-turkey-130329.htm

[2] F. D’ Andria, “Hierapolis excavation report.” Hierapolis di Frigia. Scavi e ricerche archeologiche. Published August 21, 2014. https://www.hierapolis.unisalento.it/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=e53aeaf8-8c64-4e5b-a870-fd68ee567d3a&groupId=32464352 [3] Strabo. Geography, volume VI. trans. H. L. Jones. (Harvard University Press, 1929): XIII.14 . [4] Strabo. Geography. XIII.14. trans. Jones [5] Ibidem. [6] S. E. Alcock, Archaeologies of the Greek Past. Landscape, Monuments, and Memories. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002): 22. [7] Alcock, Archaeologies of the Greek Past, 23. [8] Alcock, 28. [9] Alcock, 32. [10] F. D’Andria. “Geographical background.” Hierapolis di Frigia. Scavi e ricerche archeologiche. Last accessed December 20, 2015. https://www.hierapolis.unisalento.it/15?articolo=1. (Also for further reading on the background of the city, its history and the marvelous monuments found) [11] F. D’ Andria. “Hierapolis excavation report.” Hierapolis di Frigia. Scavi e ricerche archeologiche. Published August 21, 2014. https://www.hierapolis.unisalento.it/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=e53aeaf8-8c64-4e5b-a870-fd68ee567d3a&groupId=32464352 [12] D’ Andria. Hierapolis excavation report, August 21, 2014. [13] F. D’Andria “News Hierapolis. 26 Haziran – 7 Temmuz 2014 çalışmaları.” Hierapolis di Frigia. Scavi e ricerche archeologiche. Published August 16, 2014. https://www.hierapolis.unisalento.it/30/-/news/viewDettaglio/50285031/32464352 [14] A. Ceylan & T. Ritti. “A New Dedication to Apollo Kareios.” Epigraphica Anatolica 28, edited by E. Akurgal et al (Bonn: Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, 1997): 60. [15] These inscriptions survive thanks to a Hierapolitan that had ordered the oracles to be inscribed on stone (R. Merkelbach, 11). [16] I. Rutherford, “Trouble in Snake-Town: Interpreting an Oracle from Hierapolis-Pamukkale” in Severan Culture, edited by S. Swain, S. Harrison and J. Elsner. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007): 449. [17] Rutherford, “Trouble in Snake-Town,” 449-450. [18] Rutherford, 449. [19] Ceylan, “A New Dedication to Apollo Kareios,” 59. [20] Ceylan, 59. [21] Ceylan, 59 [22] Rutherford, 449. [23] Ceylan, 59. [24] Rutherford, 451. (translation by Rutherford) [25] Ceylan, 60. [26] Ceylan, 60. [27] Rutherford, 456. [28] M. Ricl. “Trapezonai in the Sanctuary of Pluto and Kore at Acharaca” in Ancient West & East (2013): 295-302. [29] Alcock, 1. [30] Ceylan, 65. [31] Ceylan, 65. [32] Ceylan, 65. [33] Alcock, 23. [34] Alcock, 27-28 [35] Alcock, 32. [36] Rutherford, 456. [37] Asia Minor Coins. “Hierapolis (Auton. AD 81-117) AE 25: Apollo and the Rape of Persophone.” Last accessed January 21, 2016. http://www.asiaminorcoins.com/gallery/displayimage.php?album=174&pid=5659#top_display_media%20[%2081-117%20AD%29 |

references

|

|

[1] https://www.facebook.com/Maier-Missione-Archeologica-Italiana-a-Hierapolis-di-Frigia-367057596703289/timeline?ref=page_internal [post of October 28, 2013] [2] https://www.facebook.com/Maier-Missione-Archeologica-Italiana-a-Hierapolis-di-Frigia-367057596703289/timeline?ref=page_internal [post of September 27, 2014] [3] https://www.facebook.com/367057596703289/photos/a.449609221781459.1073741825.367057596703289/449609521781429/?type=3&theater [post of April 5, 2013] [4] Merkelbach, R. & Stauber, J. “Die Orakel des Apollon von Klaros.” Epigraphica Anatolica 27, edited by E. Akurgal et al. (Bonn: Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, 1996): 4. [5] http://www.asiaminorcoins.com/gallery/displayimage.php?album=174&pid=5659#top_display_media [6] http://www.asiaminorcoins.com/gallery/displayimage.php?album=174&pid=4844#top_display_media |

images

|

|

literature

|

A.S.