The palace of

minos at Knossos

Sir Arthur Evans and the 'Palace of Minos'

|

|

The 'Palace of Minos' at Knossos is one of the most well-known excavation sites of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Its excavator sir Arthur Evans is in many ways even more famous, or infamous, because of the way he (re)constructed the 'Palace'. Arthur Evans is the epitomy of an archaeologist that was shaped by his personal circumstances and the world he lived in, which in turn shaped his excavations and the building complex he called the 'Palace of Minos'. He was living proof of the fact that archaeologists are not objective tools merely digging in the soil, rather they are like historians, interpreters of evidence.

|

Political, social and economic circumstances

There are many things that influence a person's view of the world, his/her expectations, beliefs and wishes, but also their position in life. These personal circumstances play a role in every aspect of a person's life. So, why should they not play a role in the archaeologist's mind and his views on the site he/ she is excavating?

As an archaeologist sir Arthur Evans enjoyed a certain amount of freedom that many of his colleagues did not. He was not entirely dependent on funds from the public because he could ask his wealthy father for financial aid. And when his father died he could use his inheritance to finance the digs and (re)constructions.1

Maybe even more important than his economic freedom were the political and social circumstances surroundig the excavations. When Sir Arthur Evans acquired the rights to dig at Knossos in 1894 the inhabitants of the island of Crete were engaged in a long struggle for power with their rulers, the Ottoman Empire. A civil war broke out in 1896 and lasted until 1898, when the island became an independent nation (until 1913).2

As Europe stood at the brink of the First World War, nationalism abounded everywhere. Scholarship was a source of national pride and no one wanted to fall behind in scientific discoveries. This nationalism played a role in archaeology as well.3

Accompanying nationalism was nationbuilding. Crete, the newly independent island, was looking for its own identity (apart from Mainland Greece) and it was found in the remarkable ancient ruins that sir Arthur Evans began to excavate in 1900.4 But the British nationbuilding (or rather nation stability) also came into play. Thanks to the rapid industrial transformations taking place in Europe, many countries were facing social and political upheavals that tore away at the traditional authorities and institutions.5 Authorities and institutions that sir Arthur Evans was a part of as son of a wealthy merchant.

Against the background of these instable and rapidly changing times Evans began to excavate at Knossos.

The actual excavations

Most of the excavating took place from 1900 to 1905. In later years only small discoveries were being made and from 1922 to 1930 an ambitious and far-reaching scheme of reconstruction and redecorating was begun.

Right from the start Evans seemed to jump to conclusions and gave evocative names to the chambers, architectural features and decorations he encountered. Presenting the public with an 'Ariadne fresco, ' 'the oldest throne of Europe,' a 'Throne Room,' 'The Queen's Megaron,' and the list goes on and on. Every name and fresco expressed the assumption that Evans had found the mythical Palace of Minos and a civilization that was sophisticated, ruled by an aristocratic elite and that was well-mannered and cultured.

Arthur Evans further guided the view of the public by reconstructing sections of the 'Palace'. In the beginning this was done to support the fragile walls and stairs, and to protect the frescoes and gypsum on the walls and floors from getting damaged. At first these reconstructions were done in original material like wood. But the climate of Crete proved taxing on those materials, and Arthur Evans decided to use modern materials. When Evans saw the effect the newly reconstructed parts had on the public (and himself) he began an elaborate program of (re)construstions in reinforced concrete and steel, paired with reproductions of the frescoes to decorate the walls.1

Right from the start Evans seemed to jump to conclusions and gave evocative names to the chambers, architectural features and decorations he encountered. Presenting the public with an 'Ariadne fresco, ' 'the oldest throne of Europe,' a 'Throne Room,' 'The Queen's Megaron,' and the list goes on and on. Every name and fresco expressed the assumption that Evans had found the mythical Palace of Minos and a civilization that was sophisticated, ruled by an aristocratic elite and that was well-mannered and cultured.

Arthur Evans further guided the view of the public by reconstructing sections of the 'Palace'. In the beginning this was done to support the fragile walls and stairs, and to protect the frescoes and gypsum on the walls and floors from getting damaged. At first these reconstructions were done in original material like wood. But the climate of Crete proved taxing on those materials, and Arthur Evans decided to use modern materials. When Evans saw the effect the newly reconstructed parts had on the public (and himself) he began an elaborate program of (re)construstions in reinforced concrete and steel, paired with reproductions of the frescoes to decorate the walls.1

Alternative views and additional evidence

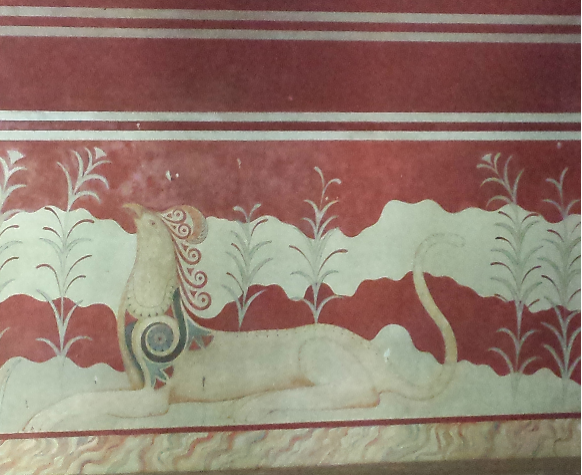

Arthur Evans has been critized for his excavations because he altered the appearance of the excavated building complex in such an elaborate way. Not only did he give the chambers and decorations poetic names that reminded people of the great British manor houses and present the public with a society that was: peaceful, loved nature and leisure, were ruled by an enlightened aristocracy, had dominion over the sea, enjoyed prosperity, and had a highly developed culture.1 He also (re)constructed entire sections of the building complex and even added features that didn't even exist in the Bronze Age, like a staircase in the southern part of the West Wing. The reproductions of the frescoes were just as 'made up' as the (re)construction of the Palace. Some images in the frescoes were made by piecing together different parts of the image, so that four or more figures formed one new figure (the 'Prince of the Lilies' fresco) and other frescoes were made by Evans' reproducer on the assumption that they must have been there because a fresco resembling it was on another wall nearby (the 'Griffin' frescoes in the 'Throne Room').2

From the 1970s onward some alternative views and additional evidence have been posed. Different views present the 'Palace' as a necropolis, a temple or a combination of temple and palace. Most scholars agree that the building complex seems to have been a manufacturing center, an administrative center with storage, a religious center and a living space.3

There has also been some new excavated evidence that alters Evans' vision of the 'Minoans'. On mount Juktas, overlooking the Knossos valley, proof has been found of a human sacrifice. And in a house in the town of Knossos the bones of two children were found with indentation marks on them, indicating that the flesh was stripped off. Some of the bones were found in a cooking pot, as if someone was making a meal out of them, suggesting that there may have been cannibalism in Bronze Age Knossos.4

From the 1970s onward some alternative views and additional evidence have been posed. Different views present the 'Palace' as a necropolis, a temple or a combination of temple and palace. Most scholars agree that the building complex seems to have been a manufacturing center, an administrative center with storage, a religious center and a living space.3

There has also been some new excavated evidence that alters Evans' vision of the 'Minoans'. On mount Juktas, overlooking the Knossos valley, proof has been found of a human sacrifice. And in a house in the town of Knossos the bones of two children were found with indentation marks on them, indicating that the flesh was stripped off. Some of the bones were found in a cooking pot, as if someone was making a meal out of them, suggesting that there may have been cannibalism in Bronze Age Knossos.4

Conclusion

As the case of sir Arthur Evans and the 'Palace of Minos' shows, archaeologists are not simply objective bystanders. Their presentation of their excavated evidence guides our views and shapes our image of places and people from long ago. This is something we need to remember when we visit an archaeological site like Knossos.

Notes

Political, social and economic circumstances:

1Christopher Scarre and Rebecca Stefoff, The Palace of Minos at Knossos (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 16.

2John C. McEnroe, “Cretan Questions: Politics and Archaeology 1898-1913,” in Labyrinth Revisited: Rethinking 'Minoan' Archaeology, ed. Yannis Hamilakis (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2002), 61. Joseph Alexander MacGillivray, Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the Archaeology of the Minoan Myth (New York: Hill and Wang, 2000), 154-155.

3McEnroe, 62.

4McEnroe, 65.

5Louise Hitchcock and Paul Koudounaris, “Virtual Discourse: Arthur Evans and the Reconstructions of the Minoan Palace at Knossos,” in Labyrinth Revisited: Rethinking 'Minoan' Archaeology, ed. Yannis Hamilakis (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2002), 52-53.

1Christopher Scarre and Rebecca Stefoff, The Palace of Minos at Knossos (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 16.

2John C. McEnroe, “Cretan Questions: Politics and Archaeology 1898-1913,” in Labyrinth Revisited: Rethinking 'Minoan' Archaeology, ed. Yannis Hamilakis (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2002), 61. Joseph Alexander MacGillivray, Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the Archaeology of the Minoan Myth (New York: Hill and Wang, 2000), 154-155.

3McEnroe, 62.

4McEnroe, 65.

5Louise Hitchcock and Paul Koudounaris, “Virtual Discourse: Arthur Evans and the Reconstructions of the Minoan Palace at Knossos,” in Labyrinth Revisited: Rethinking 'Minoan' Archaeology, ed. Yannis Hamilakis (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2002), 52-53.

The actual excavations:

1Scarre and Stefoff, 27-28. MacGillivray, 232-233. Hitchcock and Koudounaris, 41.

1Scarre and Stefoff, 27-28. MacGillivray, 232-233. Hitchcock and Koudounaris, 41.

Alternative views and additional evidence:

1McEnroe, 69. MacGillivray, 195. Hitchcock and Koudounaris, 54.

2MacGillivray, 203-204. Rodney Castleden, The Knossos Labyrinth: A new view of the 'Palace of Minos' at Knossos (London & New York: Routledge, 1990), 33-34.

3Castleden, 46-95. J. Lesley Fitton, Peoples of the Past: Minoans (London: The British Museum Press, 2002), 71-72 and 134-135.

4Fitton, 102-105 and 138.

1McEnroe, 69. MacGillivray, 195. Hitchcock and Koudounaris, 54.

2MacGillivray, 203-204. Rodney Castleden, The Knossos Labyrinth: A new view of the 'Palace of Minos' at Knossos (London & New York: Routledge, 1990), 33-34.

3Castleden, 46-95. J. Lesley Fitton, Peoples of the Past: Minoans (London: The British Museum Press, 2002), 71-72 and 134-135.

4Fitton, 102-105 and 138.

Bibliography

Castleden, Rodney. The Knossos Labyrinth: A new view of the 'Palace of Minos' at Knossos. London and New York: Routledge, 1990.

Hitchcock, Louise and Paul Koudounaris. “Virtual Discourse: Arthur Evans and the Reconstructions of the Minoan Palace at Knossos.” In Labyrinth Revisited: Rethinking 'Minoan' Archaeology, ed. Yannis Hamilakis, 40-58. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2002.

Lesley Fitton, J. Peoples of the Past: Minoans. London: The British Museum Press, 2002.

MacGillivray, Joseph Alexander. Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the archeology of the Minoan myth. New York: Hill and Wang, 2000.

McEnroe, John C. “Cretan Questions: Politics and Archaeology 1898-1913.” In Labyrinth Revisited: Rethinking 'Minoan' Archaeology, ed. Yannis Hamilakis, 59-72.

Scarre, Christopher and Rebecca Stefoff. The Palace of Minos at Knossos. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Hitchcock, Louise and Paul Koudounaris. “Virtual Discourse: Arthur Evans and the Reconstructions of the Minoan Palace at Knossos.” In Labyrinth Revisited: Rethinking 'Minoan' Archaeology, ed. Yannis Hamilakis, 40-58. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2002.

Lesley Fitton, J. Peoples of the Past: Minoans. London: The British Museum Press, 2002.

MacGillivray, Joseph Alexander. Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the archeology of the Minoan myth. New York: Hill and Wang, 2000.

McEnroe, John C. “Cretan Questions: Politics and Archaeology 1898-1913.” In Labyrinth Revisited: Rethinking 'Minoan' Archaeology, ed. Yannis Hamilakis, 59-72.

Scarre, Christopher and Rebecca Stefoff. The Palace of Minos at Knossos. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Image source citations

Image of the bull-fresco taken from www.fanpop.com/clubs/ancient-greece/images/31794823/title/palace-knossos-photo

Image of the griffin-fresco is one of my own photo's.

Image of the griffin-fresco is one of my own photo's.

Written by D.M.P. on 29 january 2016