Petra

water(works) in the desert

Abstract

(1) The location of Petra in modern day Jordan

(1) The location of Petra in modern day Jordan

In this article, the water works of the Nabataean city of Petra will be discussed. Water was on display throughout the city, with larger structures focused around the city center. Besides their public and religious function, I will discuss whether or not these water works served a different purpose: ostentatious display of wealth and status. The term ‘conspicuous consumption’ or ‘conspicuous waste’ is used to investigate these water works. The location and context of the display will be mentioned as well. Crucial evidence forms the ‘recently’ discovered pool-complex in the heart of the city, a large man-made, (probably) recreational pool. Two artificial waterfalls are vital evidence as well, given their location (in full public view), context and wasteful nature. In the arid desert climate of Petra, water was a bare necessity and a luxury item at the same time, and its display added to the beauty of the city.

Introduction

|

|

The Nabataean city of Petra was declared a world wonder in 2007, and throngs of tourists visit it every year. With its rock hewn monumental facades, this beautiful city is an engineering and architectural marvel. But in ancient times the city was known for something completely different. As Strabo writes around 9 BCE: ‘[…] in the outside parts of the site being precipitous and sheer, and the inside parts having springs in abundance, both for domestic purposes and for watering gardens.’ (Geog.XVI.4.21). The desert city was known for its display of water.

In 1998 scientists were amazed to discover a large manmade pool. This leads to my research question: ‘In what way was water displayed in Nabataean Petra, and, is it a case of ‘conspicuous consumption’? The latter term was coined by 19th century economist and sociologist Thorstein Veblen [1]. He says that when a person or a society has established safely the fundamental requirements (food, shelter, security) any further accretion of wealth or income will be applied not to rational objectives of usefulness or amenity, but to ostentation and display. This article is meant as a case study, showing the different monuments in Petra displaying water, and trying to answer whether or not it’s a case of ‘conspicuous consumption’. I’ll look into the monuments themselves and their location in the city. This research is limited to a few buildings and monuments dating from the Nabataean period from first century BCE to CE, with a small exception from the Roman period (after 106 CE). |

The Nabataeans: 'Masters of the desert'

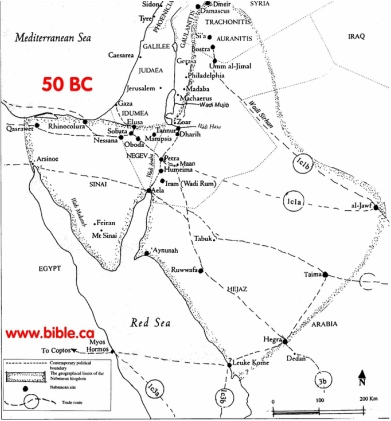

(2) The Arabian peninsula, with the (frankincense) trade routes, and size of the Nabataean kingdom at its heyday

(2) The Arabian peninsula, with the (frankincense) trade routes, and size of the Nabataean kingdom at its heyday

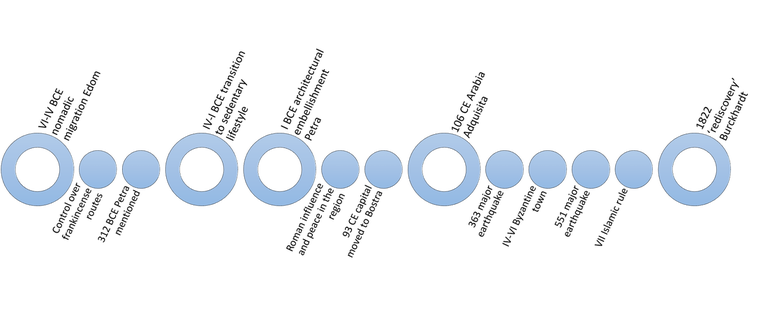

The nomadic Nabataeans started migrating to the region around the sixth century BCE, and quickly gained hold of the trading routes that were abundant through the desert land [2]. The dominant trade was frankincense, which had many uses in ancient times [3]. The trading business turned out very lucrative. Slowly the Nabataeans started to settle permanently. Their stronghold at the foot of the mountain Umm al-Biyara [4] was turned into their capital Petra [5], first mentioned around 312 BCE. They also came into contact with many cultures, as can be seen in the Hellenistic, Egyptian, Persian, Assyrian and Roman influences on their architecture [6].

The expansion of the Nabataean kingdom was halted by the Romans from the first century BCE on, a growing influence in the area. Roman presence established peace and prosperity. During this century, an enormous embellishment of the Nabataean cities, especially Petra, is witnessed. Nonetheless, the trade routes slowly started to move, and Bostra in the north was made capital in 93 CE. In 106 the kingdom was incorporated into the Roman Empire, probably by testamentary means of the last king [7].

The expansion of the Nabataean kingdom was halted by the Romans from the first century BCE on, a growing influence in the area. Roman presence established peace and prosperity. During this century, an enormous embellishment of the Nabataean cities, especially Petra, is witnessed. Nonetheless, the trade routes slowly started to move, and Bostra in the north was made capital in 93 CE. In 106 the kingdom was incorporated into the Roman Empire, probably by testamentary means of the last king [7].

Hydraulic ENGINEERING

The desert has a very arid climate, with rainfall under 10 cm per year (often between 2.5 and 7.5 cm), and long summers from April to October, dry as a bone [8]. Rainfall and a few springs in- an outside the city were the only water supply. Flooding due to heavy winter rainfall presented a problem: the narrow passageway to the city, the Siq, must have been a deathtrap during the flashfloods [9]. Over time the Nabataeans developed an elaborate system dedicated to the containment, capture, storage, transportation and distribution of water, providing water ‘on-demand’ all year round [10]. They also needed an elaborate bureacracy to manage and maintain the flow of information of this fast evolving complex infrastructure [11]. According to Ortloff, the amount of water available per capita was just little under that of Rome, around 600 liters per day per person (Petra had an estimated population of 30,000) [12]. This extreme hydraulic engineering earned the Nabataeans the epithet ‘Masters of the Desert’.

Religious water

|

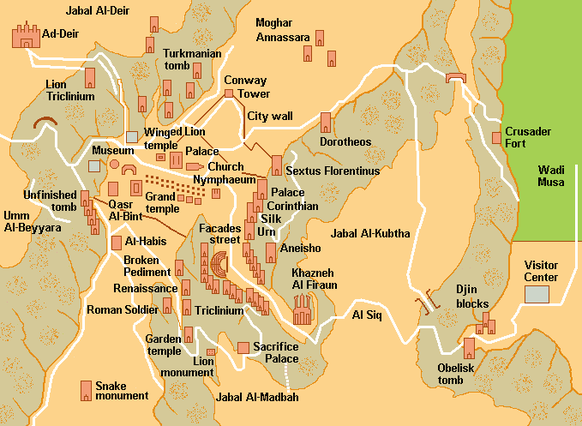

Besides survival and basic hygiene, water played a big role in the social, political and religious life of Petra. Water for religious purposes was on display throughout the city. Many religious symbols have been found in the Siq. Lined with pipelines used to transport water in to the city, and controlling flood water, the narrow (sacred) passage in to the city must have resonated with the sound of water [13]. Water and religion are more closely linked in other monuments. En route to the ‘High Place of Sacrifice’ (see map) stood a fountain dedicated to the goddess of water and fertility. It stood 4.5 meters high and was carved in the shape of a lion, the water flowing from its mouth.

Another example of (religious) water on display is the Nymphaeum, built in the Roman period. Although the religious origin of the public fountain may have been lost to travelers, it did stand near the ‘Winged Lion Temple’ on the Colonnaded Street (see map). At the heart of the market areas, urban core and close to religious buildings, the large basin was filled by as many as 3 different sources, showing the importance of keeping it filled [14]. The volume of water was a status marker for the city [15]. |

Pool & Garden complex

During excavations in 1998, the so-called ‘Lower Market’ (see map) had a surprise in store for archaeologists: a large pool 43 x 23 and 2.5 m deep was discovered [16]. The ‘Lower Market’ had been wrongfully identified in a German expedition in 1921. We know believe that the place held a large pool with island pavilion (11.5 x 14.5) and an adjacent ornamental garden.

Gardens and (swimming) pools weren’t unknown in the ancient world. In the Egyptian, Mesopotamic, Persian and Hellenistic world, gardens and pools were used for religious and political purposes. But the pool al Petra most likely wasn’t sacred. Firstly, the religious context is missing. The Great Temple next to it was most likely misidentified: it has no religious accouterments (altar, dedicatory inscriptions, artifacts), and its plan is very unlike other Nabataean temples [17]. It was probably used as an audience hall, and might have been part of a larger royal complex. Secondly, evidence comes from the several palaces built by Herod the Great (37-4 BCE) king of Judea. These contained pools for recreational purposes [18]. The pool-complex and Herod’s pleasure garden at Herodium are almost identical. There was a lot of rivalry and intermarriage between the Nabataean and Herodian royal families [19].

Bedal rightfully states that even though the Nabataeans had excellent water management, due to the growing population, they didn’t have any excess water. Still they made the choice to build a large (recreational) pool. Given the location in the political, commercial and religious core (the Winged Lion Temple looked over the complex), the pool and garden must have been a strong statement to incoming foreigners: Petra is a rich and thriving metropolis.

Gardens and (swimming) pools weren’t unknown in the ancient world. In the Egyptian, Mesopotamic, Persian and Hellenistic world, gardens and pools were used for religious and political purposes. But the pool al Petra most likely wasn’t sacred. Firstly, the religious context is missing. The Great Temple next to it was most likely misidentified: it has no religious accouterments (altar, dedicatory inscriptions, artifacts), and its plan is very unlike other Nabataean temples [17]. It was probably used as an audience hall, and might have been part of a larger royal complex. Secondly, evidence comes from the several palaces built by Herod the Great (37-4 BCE) king of Judea. These contained pools for recreational purposes [18]. The pool-complex and Herod’s pleasure garden at Herodium are almost identical. There was a lot of rivalry and intermarriage between the Nabataean and Herodian royal families [19].

Bedal rightfully states that even though the Nabataeans had excellent water management, due to the growing population, they didn’t have any excess water. Still they made the choice to build a large (recreational) pool. Given the location in the political, commercial and religious core (the Winged Lion Temple looked over the complex), the pool and garden must have been a strong statement to incoming foreigners: Petra is a rich and thriving metropolis.

Water wasting waterfalls

One of the most striking examples of water on display were two (maybe more) waterfalls, a third one in a suburb of Petra. During raining season many natural waterfalls could be witnessed. A 4 meter high artificial waterfall lied next to the Pool Complex [20]. At its base a series of terraced basins and channels transported water to the pool and gardens. Another one was next to the beautiful ‘Royal Tombs [21]’, high on a ridge overlooking the city (see map and photo's). This waterfall was 20 (!) meters high, and carved in to the sandstone cliff. At the bottom the water was again caught and transported somewhere, perhaps to the Nymphaeum.

Waterfalls, like the public pool and fountains, have many functions: providing a cooling mist, cleansing insects from the water’s surface and the splashing sounds drowned the noise from the streets. But they have a very negative outcome on water conservation, especially the 20 metre one. The Nabataeans had ways of efficiently transporting water, ceramic pipe-lines, covered channels etc. Given their prominent location in the city center (the ‘Royal Tombs’ waterfall towering over busiest streets) and their wasteful nature, these waterfalls must have been made for display purposes. The aesthetics and the impressive display must have been worth it.

Waterfalls, like the public pool and fountains, have many functions: providing a cooling mist, cleansing insects from the water’s surface and the splashing sounds drowned the noise from the streets. But they have a very negative outcome on water conservation, especially the 20 metre one. The Nabataeans had ways of efficiently transporting water, ceramic pipe-lines, covered channels etc. Given their prominent location in the city center (the ‘Royal Tombs’ waterfall towering over busiest streets) and their wasteful nature, these waterfalls must have been made for display purposes. The aesthetics and the impressive display must have been worth it.

To conclude

Water was on display throughout the city of Petra, with larger monuments (pools, fountains) in the civic center. It is important to note that function and ostentatious display are not mutually exclusive. The monuments listed did serve utilitarian and religious purposes, they were not purely decorative. Nonetheless, their location in the city, clearly visible to (foreign) visitors and inhabitants, and their size and wasteful nature, especially the waterfalls, indicates that they were also used for displaying wealth and status. In the harsh, arid climate of the desert, water is extremely valuable. Spending such a large amount of water on anything more than survival and basic use, tells a bigger story. At the nexus of the trading routes, surrounded by many (rivaling) cultures and nations, Petra was visited by many. And the ostentatious, wasteful display of water told them: the Nabataeans have the wealth and the status to use valuable water as a luxury item.

NOtes

[1] Ryan (2007) 127-128

[2] Taylor (2002) 14, Bedal (2003) 4-9

[3] Taylor (2002) 19

[4] meaning ‘Mother of Springs’

[5] Petra comes from the Greek word πετρα, meaning ‘rock’. The Nabataean name for their capital was Reqem, deriving from the semitic root rqm, meaning ‘variegated’. This likely reffered to the multi-colored landscape. Bedal (2003) 5

[6] Taylor (2002) 111

[7] Bedal (2003) 13-14, Taylor (2002) 74

[8] Bedal (2003) 87

[9] Taylor (2002) 19

[10] see Ortloff (2005) for a detailed listing of this system, and Mithen (2010) for an historic overview of water management in the Jordan valley.

[11] Ortloff (2005) 97

[12] ibidem 107

[13] Bedal (2003) 97-99

[14] Ortloff (2005) 99, 100, 103

[15] Bedal (2003) 101, Ortloff (2005) 103

[16] see Bedal (2003) and Bedal (2001) for more information on the excavations.

[17] Bedal (2003) 38

[18] ibidem 37-39

[19] Josephus Jewish Wars I.8.9, 13-29

[20] Bedal (2002) 230-232

[21] The idea that the structures known as the ‘Royal Tombs’ were actually tombs is attested.

[2] Taylor (2002) 14, Bedal (2003) 4-9

[3] Taylor (2002) 19

[4] meaning ‘Mother of Springs’

[5] Petra comes from the Greek word πετρα, meaning ‘rock’. The Nabataean name for their capital was Reqem, deriving from the semitic root rqm, meaning ‘variegated’. This likely reffered to the multi-colored landscape. Bedal (2003) 5

[6] Taylor (2002) 111

[7] Bedal (2003) 13-14, Taylor (2002) 74

[8] Bedal (2003) 87

[9] Taylor (2002) 19

[10] see Ortloff (2005) for a detailed listing of this system, and Mithen (2010) for an historic overview of water management in the Jordan valley.

[11] Ortloff (2005) 97

[12] ibidem 107

[13] Bedal (2003) 97-99

[14] Ortloff (2005) 99, 100, 103

[15] Bedal (2003) 101, Ortloff (2005) 103

[16] see Bedal (2003) and Bedal (2001) for more information on the excavations.

[17] Bedal (2003) 38

[18] ibidem 37-39

[19] Josephus Jewish Wars I.8.9, 13-29

[20] Bedal (2002) 230-232

[21] The idea that the structures known as the ‘Royal Tombs’ were actually tombs is attested.

References

Akasheh, T. S. (2002). Ancient and modern watershed management in Petra. Near Eastern Archaeology, 65(4), 220.

Bedal, L. A. (2001). A pool complex in Petra's city center. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 23-41.

Bedal, L. A. (2002). Desert oasis: Water consumption and display in the Nabataean capital. Near Eastern Archaeology, 65(4), 225.

Bedal, L. A. (2003). The Petra Pool-Complex. Gorgias Press.

Mithen, S. (2010). The domestication of water: water management in the ancient world and its prehistoric origins in the Jordan Valley. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 368(1931), 5249-5274.

Ortloff, C. R. (2005). The water supply and distribution system of the Nabataean city of Petra (Jordan), 300 BC–AD 300. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 15(01), 93-109.

Ryan, P. (2007). Thorstein Veblen and Conspicuous Consumption. QUADRANT, 51(1/2), 127-128.

Taylor, J. (2001). Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans. IB Tauris.

Bedal, L. A. (2001). A pool complex in Petra's city center. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 23-41.

Bedal, L. A. (2002). Desert oasis: Water consumption and display in the Nabataean capital. Near Eastern Archaeology, 65(4), 225.

Bedal, L. A. (2003). The Petra Pool-Complex. Gorgias Press.

Mithen, S. (2010). The domestication of water: water management in the ancient world and its prehistoric origins in the Jordan Valley. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 368(1931), 5249-5274.

Ortloff, C. R. (2005). The water supply and distribution system of the Nabataean city of Petra (Jordan), 300 BC–AD 300. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 15(01), 93-109.

Ryan, P. (2007). Thorstein Veblen and Conspicuous Consumption. QUADRANT, 51(1/2), 127-128.

Taylor, J. (2001). Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans. IB Tauris.

Images

(header) http://www.airpano.com/Photogallery.php?gallery=58&photo=1262

(1) https://excitingearth.wordpress.com/category/man-made/

(slide show)Touristic highlights of Petra, photographs by author

(2)http://www.bible.ca/archeology/bible-archeology-exodus-kadesh-barnea-petra.htm

(3)https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petra#/media/File:Karta_Petra.PNG

(4) http://www.voyagevirtuel.info/jordanie/bigphotos/petra-zib-attuf_132.jpg

(5)http://www.walkingeurope.info/walks/walks/walk_photo/613204/

(6)http://www.personal.psu.edu/faculty/l/x/lxb41/maps.html

(7)https://petragardenexcavation.files.wordpress.com/2013/05/garden-w-red-pavilion-1998-ck.jpg

(8)http://clfrancisco.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/PetraReconstructionCityCtr.jpg

(9)https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Joukowsky_Institute/Petra/excavations/2006-adaj.html

(10)http://www.soniahalliday.com/category-view3.php?pri=J146-9-85JT.jpg

(1) https://excitingearth.wordpress.com/category/man-made/

(slide show)Touristic highlights of Petra, photographs by author

(2)http://www.bible.ca/archeology/bible-archeology-exodus-kadesh-barnea-petra.htm

(3)https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petra#/media/File:Karta_Petra.PNG

(4) http://www.voyagevirtuel.info/jordanie/bigphotos/petra-zib-attuf_132.jpg

(5)http://www.walkingeurope.info/walks/walks/walk_photo/613204/

(6)http://www.personal.psu.edu/faculty/l/x/lxb41/maps.html

(7)https://petragardenexcavation.files.wordpress.com/2013/05/garden-w-red-pavilion-1998-ck.jpg

(8)http://clfrancisco.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/PetraReconstructionCityCtr.jpg

(9)https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Joukowsky_Institute/Petra/excavations/2006-adaj.html

(10)http://www.soniahalliday.com/category-view3.php?pri=J146-9-85JT.jpg

Author: E.N. 28-01-2016